Organizational art

Week 43: A Constructed World

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is another event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

This week we’ll be talking with Geoff Lowe, Jacqueline Riva and a half dozen or so other members of A Constructed World.

http://www.aconstructedworld.com

http://speech2012.blogspot.com/

http://telic.info/node/37

A Constructed World make whatever they make — events, installations, videos, drawings and publications — using the media of not-knowing, idle banter, pamphleteering, live eels, dancing, absences and errors, sleight-of-hand and mistakes. In addition to talking about their projects over the years, which has focused largely on raising the question “what is a group?” collectively, and approaching working with other people as constituting what psychoanalysts call a shared space of “not-knowing”, the group will discuss their recent “Fragments in A Constructed World” project, premised on the hypothesis that there may be a lot of unknown overlaps, or potential points of shared interest between people who aren’t aware of that yet. The project has entailed setting up spaces for dialogue, using fragments of Morse code, Chinese pictograms, telepathy… In fact, this week’s discussion will be an open-ended instantiation of the project, even as the group discusses specific tangible methods and infrastructures which they have set up.

This is of course all very much in the spirit and undefined ambit of Plausible Artworlds, which by design is committed to the idea that all (art)worlds are constructed worlds — yet in both popular and learned parlance to describe a world as “constructed” is not trivially tautological. Why is it that worlds appear invariably natural to those operating in them? Or do we “not-know” they are constructed as a form of knowing? Perhaps this is the key to the experimental epistemology of not-knowing. Who knows? And by extension, who brings what to group making? What form of not-knowing do artists — or other categories of not-knowers — bring to world-construction sites?

Transcription

Week 43: A Constructed World

[0:00:00]

Male speaker: Hey Scott.

Scott: Hello there.

Male speaker: How is it going men?

Male speaker: Hey how are you?

Male speaker: All good.

Jackie: Hi Scott?

Scott: Hello everyone?

Male speaker: You hear me? Hey Jackie.

Jackie: My God [0:00:16] [inaudible] how are you?

Male speaker: I’m good.

Jackie: Good to [0:00:20] [inaudible] you.

Male speaker: Sorry?

Jackie: Good to hear you.

Male speaker: Me too good to hear you.

Jackie: Yeah.

Male speaker: Is Jeff there?

Jeff: Yes I’m right here, I’m right here.

Male speaker: Hey.

Jackie: You know how I was making some telepathy with my—my art students today and I showed them the word fang.

Male speaker: Oh cool.

Jackie: Yes and they knew a lot of the meanings of the word.

Male speaker: Oh really?

Jackie: Yes it was very...

Male speaker: Maybe because they are Chinese.

Jackie: Yeah.

Male speaker: Sure.

Male speaker: Part of the reason.

Male speaker: Well it’s appropriate that tonight’s chat is going to talk not only about a constructive world but about fragments because it sort of started out that way.

Male Speaker: Are you there Mathew?

Mathew: Yes I just had my thing on mute, hello everyone?

Jackie: Hi Mathew.

Male speaker: Hello Mathew.

Male speaker: [0:01:27] [inaudible] sorry Scott.

Male speaker: Oh not at all Welcome everyone to our humble weekly chat. The context is of this year—

Jackie: [0:01:41] [inaudible] there?

Male speaker: Sorry?

Jackie: Is Mathew and Antoine there?

Male speaker: Oh right I think Antoine is at basekamp.

Jackie: Right.

Male speaker: There we go, he is texting in. Then I believe they are waiting on Mathew and a few other people to show up to the basekamp space.

Jackie: Right.

Male speaker: Yeah I guess there is some kung fu going on pretty loud but yes you can always unmute and say hello any time Antoine. But yes so I’m really glad that you were able to join us tonight especially some of you it’s incredibly late where you are and you know we are always happy that people are able to actually either get out of bed in the middle of the night or stay up really late or wake up really early to join this. Or like in the middle of the afternoon which could be equally unpleasant sometimes, Jeff thanks. And so yes, so welcome to another week in the series of chats about different examples of kinds of plausible art worlds or what we are calling plausible art worlds, this year.

We are talking with Jacqueline Riva and Jeff Lowe about I guess a number of other people involved with the constructed world, about A Constructed World and your practices over, you know over the last 15 or quite—actually I should have come with a good way to introduce that but over quite a long period of time that you have been investigating this [0:03:30] [inaudible]. What is the group and you have been addressing this in lots of different ways. For the people that are—I think and a lot of us do know you and already work with you but for the people here that aren’t aware yet of what you do would you mind giving us a brief intro to why and how A Constructed World got started?

Male speaker: Well I’m thinking when you invited this for to just start with what we’d proposed that’s it’s almost like we’ve already started what I was going propose tonight.

Male speaker: Okay.

Male speaker: Like there is the way this conversation started was an example but I mean maybe the fastest was to explain that the first things that Jackie and I did together was we made a Art magazine that ran for ten issues and we invited people who said they didn’t know about art or contemporary art to write about contemporary art. So it’s just been like an ongoing that that we’ve looked at this in all sorts of different ways of thinking what not knowing is or what saying you don’t know is or how you can move between ignorance and knowing or resistance to knowing or even innocence of knowing and knowledge like in the case of Adam and Eve and things like that.

[0:04:56]

So that’s sort of been what we are interested in. but we recently did a performance which quite a few of the people at Rome [0:05:04] [inaudible], we at the [0:05:08] [inaudible] in Paris. And we did a project where we had all different forms of communication coming in to the space at the same time which we have planned to do tonight. So we had, Hal sent us some Chinese characters which we couldn’t , which nobody could understand and then we showed them all to the audience and then later we read out the mulit-often really multiple meanings of them. We had Sean and Veronica who are in Melbourne know and doing this and they sent us in Paris a telepathy message.

Male speaker: Are they sending telepathy at the moment?

Male speaker: Yes they are sending, I have it on good [0:06:03] [inaudible] they send me some now.

Male speaker: Okay.

Male speaker: And we can find out later what that was. And then well we have had a number of—I had Morse code which if anyone’s interested I can play it again for you tonight.

Male speaker: Great.

Male speaker: That we had a conversation that commands someone else that we were working with, and that Marie who read out a text and Mathew has a text, Mathew Raner who is with us. That it would be great if he could either read out of it or talked to us about it. So what we would I guess try to just think about is that, I mean it’s pretty obvious in a way that if everything’s so full and you don’t really know what you are doing which is a kind of pretty common way of operating now, that there is far too much information and that you usually don’t understand most of what’s going on.

And so what we are kind of interested to think about is to think about that can that be a shared space. So if we mutually don’t know what we are doing together could that exist in the space we could be occupying in any kind of collective or perhaps collaborative way. And so I guess just a very—I have never really been on such a large chat of course if any have there been too big before but I kind of just by the chaos of how we started I guess it has this kind of a feeling already so.

Male speaker: Its coming through very clearly though.

Male speaker: What’s that?

Male speaker: The audio is coming through very clearly.

Male speaker: Okay good.

Stephen: Jeff can I ask you a question its Stephen here, so that this collective space of understanding actually functions, it’s important that nobody understands the Chinese characters, that nobody really knows anything about telepathy and that the Morse code can’t be deciphered right? Because of course if it--.

Jeff: Yeah.

Stephen: Yeah.

Jeff: So in the sense that…

Jackie;Well I don’t think that, I mean that’s not necessarily the case because of course we all come to the group or come to an event with different experiences. And so there maybe people in the group who have been making telepathic passes or experiments, there maybe people in the group who do understand Chinese. So the thing is that we, you know what we are really working with is the experience of the people in the group and what that inevitably does is bring together quite a bit of knowledge. So we start from the point of not knowing but you don’t really end up in a situation of not knowing once you have engaged in an activity or some kind of experience together.

Male speaker: Yes well I guess that’s right I mean I was just about to agree with you Stephen so that’s interesting right? It’s really interesting because what we kind of supposed about art is that it’s kind of impossible to not know about art in the end and that often people once they would say oh I don’t know anything and then offer an opinion, they’d kind of say something that was often more compelling that what the art could exhibit and on the same page. So yeah like I suppose we are just trying to think how to further this that if you don’t understand things where are you?

Jackie: Yes well I think that after or by the time we got to 10 issues of the magazine what we considered that we had done was to make a research. And going back you know occasionally I go back and read one of the magazines and what I realized was that in fact the people who said that they didn’t know about art certainly did know something when they were writing about it. And…

[0:10:37]

Male speaker: So does that mean I know Chinese?

Jackie: Well I think, you know that’s a different, I mean no I don’t think you know Chinese I haven’t seen any evidence of that yet but you know certainly you know the way that people wrote about—I mean I think the thing is that we live in a very sophisticated manner because we grew up with television and we understand how to read images and with internet and changing the channel and we have a very sophisticated mode of reading things, reading signs. And you know signifies and all this kind of thing and so when you finally get to the point of looking at an art work for someone who hasn’t been trained you know, who thinks that they don’t know anything about it, they still have a very sophisticated language of how to read signs and symbols. So you know there is something that’s there from the way that we all engage in society and in the community that we live and in the kind of world that we live in.

Male speaker: Yes anybody out there?

Male speaker: Yes definitely.

Male speaker: Well I mean the example that we used to use a lot like that was that if a person has a remote control watching the television and even someone who has almost no education that they make incredibly informed visual decisions in you know really a portion of a second and they can flick the channel and decide what period, what genre, what type of show it is. And you know like numerous categories and just sum it up really in a part of a second. And so that is a lot of, you know, visual acumen to be able to do that. And yeah so like how is that perhaps joined to how people might interface with what we have come to call contemporary art?

Male speaker: So you guys see, you make very little distinction between creativity from people or so called creativity or whatever term you want to use, imaginative, oh I don’t know, perception or whatever, by people who are trained in art and people who are not.

Male speaker: Well I think the thing that we thought a lot about lightly was that what we would try to do was that we would try to write a bigger repertoire for the audience to work with, because at the moment we’ve got a kind of situation where the artist has this you know possibility to be in movement and to be changing media and changing ways of working to be moving and to be nomadic and things like that. Whereas the audience is still expected to be constituted and know what they think and to have an opinion and that’s why people are thinking the audience feels really intense pressure as though that they should know something like that.

Whereas it’s been acceptable for a long time like from the modern artist and like John Coltrane or Roscoe or people or you know, to not know what they were doing and to put that forward as a methodology. Whereas somehow the way that the audience seems to face doesn’t allow that, it’s not allowed. So yeah this was what we were trying to think about is that you know what can you say when you don’t know you know? Or could we be together when we don’t know in this kind of way?

Stephen: I’ve got about, hi Stephen again sorry to jump in again but I’ve got about six billion questions already okay.

Male speaker: Okay.

Stephen: Can I just ask like maybe one of those questions? Is this kind of based on the experience like this morning I was in the Metro in Paris and I had two weird experiences of people not knowing things and maybe three actually. Okay and they are three very different kinds, one was this guy, an African guy who was illiterate and who was trying to—he needed to buy something but the guy who was selling it to him would refer him systematically to the, like the sign of what was for sale. And the guy wasn’t interested in what the sign said because he couldn’t read it, he wanted an explanation of what actually the guy was selling and he wasn’t very forthcoming about that.

[0:15:33]

So obviously a person who is illiterate and we have all seen it and he can negotiate a world of signs and semiotic in an incredibly sophisticated way without actually using those signs in the way that the rest of the user ship can. Are you talking about that? or the second scenario was this blind guy who was not, obviously hadn’t been blind for long because he was making his way very inadequately through the Metro system, waving his white cane like far too widely, hitting people with it and stuff. It was kind of funny in an uncomfortable sort of way. But it reminded everybody I guess that, like this is not about illiteracy this is about something which has happened to him which has deprived him of what in our civilization is the primary sense, the sense of vision and he was not accustomed to using his other senses.

And then in a more banal way the guy who was sitting next to me in the metro turned to me at a certain moment, this is like at 7:00 in the morning I’m trying to think about how to write up the blurb for this conversation tonight. And the guy says can you tell me in French is the word K like where you stand to get on the train, is that masculine or feminine? So that was kind of non-knowing which is like the guy was completely familiar with our visual semiotic, he was obviously literate because the reason he wanted to know that answer because he was using his Blackberry he was typing an SMS to somebody and wanted to tell them about something, all he needed to do was not pass for somebody who didn’t really know how to speak French very well.

So there is three kinds in a few moments of totally different unknowing, how do you deal that, you know that the equivalence of intelligence that we all share that makes it impossible to share a world, to construct a world. Which type of non-knowing are you interested in or how do you differentiate?

Male speaker: Well I think this is what Jackie was perhaps talking about he said it’s still very much a risk we are just working on case studies really. And so those are all perfectly you know, good and implicit case studies. And the other one I mean obviously there is many others but then there is also like the passion for ignorance where people deliberately pretend to not know things because it gives them advantages. And yes there is a lot of that in politics in that at the moment where people pretend to be a lot more ignorant of information than what they actually are so it’s kind of like a strategic not-knowing as well.

And so it’s a kind of question of that what we are looking is could this be a space rather than an absence in this kind of sense. That could be a space where it kind of could be occupied. I mean one of the things that we hadn’t start [0:18:34] [inaudible] that was talked about quite a lot is that Nicha says this thing that he didn’t read books and that he criticized other intellectuals for reading because they were getting the wrong kind of way of entering things. And you know so we thought this was really interesting, did that mean that other people who didn’t read books could be considered to be in the same space and Nicha sort of thing.

Male speaker: And guys there is a continual emphasis, sorry I’m just traveling at the ongoing text chat here. There is a continual emphasis on approaching knowing as a group in some way. As if like you said it’s not as if we are pretending to or sort of feigning ignorance or somehow [0:19:41] [indiscernible] things that we have learned or experienced. But that this kind of maybe removal of an idea of knowing might help us reproach a space together and have a different kind of knowing.

[0:19:58]

Male speaker: Yeah well like I mean it’s to do as [0:20:00] [indiscernible] in that kind of sense and maybe it’s to do with the kind of the unconscious of the audience you know? That the audience could not know in that kind of sense just like Van Gogh had an unconscious or you know famous artists have an unconscious that the audience could be working with their unconscious [0:20:24] [inaudible] as well. And so is this someway that we can try and make a picture of where this place instead of outside our immediate grasp but obviously there where they are if that makes any sense you know. Like in terms of psychoanalysis or something where these places are reliably there and have a kind of presence in all sorts of different ways but necessarily, you know slipped, you know, [0:20:57] [indiscernible] and away from us.

But then there is also at the moment like I was saying, well I’ll stop talking after this, but about this idea of you know the kind of disingenuous subject where I was reading, there is this would – be senator in America and she is like part of this [0:21:17] [inaudible] and she said that she doesn’t believe that in masturbation as a sort of blanket statement sort of thing. And it just seemed like such an incredible thing to say and it’s almost like sort of willfully saying something that can’t be possible that will bring a lot of other people aboard sort of thing.

So that we can sort of say things that we in a way know aren’t true or my last example would be in Australia we had what they call the dog whistle politics. Where the politician would say something that was in fact racist or something that wasn’t on the page [0:22:01] [inaudible] that all of the people would come to know that it was you know? So yes, so there is all this place outside of what we are saying that kind of could be vacant in different ways. So just say that Mathew, what is it that you said? Are you there Mathew?

Male speaker: Yes Mathew do you want to say that over audio or would you like someone else to read it out?

Mathew: Are you talking to me Mathew or the other Mathew who is in Philadelphia?

Male speaker: We are talking to you.

Mathew: Okay.

Jackie: Mathew Raner.

Mathew: Hi.

Jackie: Hi.

Mathew: Yes I was trying to, you know fragment the conversation a little bit with this magic text.

Male speaker: Yes.

Mathew: So that was just what I was doing.

Male speaker: And so do you want to just tell us something though in audio rather than in the written?

Mathew: Sure, I mean you know I guess just I mean listening to you, this you know one thing I was thinking I have been trying to follow both the audio and the text. But you know the kind of strategic not knowing or something like that I was thinking also about kind of how we are trained to read things like as a text in this way and this sort of space of not knowing I think like this Nicha I guess not reading books I guess sort of a—it’s not like a willful ignorance but it’s trying to sort or maybe escape some of the kind of binary, the binaries of like signifier and signified and things like this. So it’s, yes it’s a big question, I’m sorry it’s a little late here in Sweden.

Male speaker: No, not at all.

Male speaker: Mathew we fully expect you to know exactly what to say.

Mathew: Exactly so in any case I feel like I’m a little bit more prepared on the text end of things than the audio.

Feale speaker: So will you read your text Mathew?

Mathew: Sure if you prefer it read.

Male speaker: We would like that because I have got an audio from comontse [phonetic] [0:24:49] that I was going to play. So we would like it if you’d read some of it out or all of it whichever you prefer.

Mathew: So I suppose that you know I could try to contextualize this a little bit, it came out of the event in Belleville in Paris when we were meeting with the speech and what archive which is kind of another aspect I guess of your practicing. I know you haven’t really discussed but it’s just thinking about how speech can kind of maybe be documented or kind of have a longer life than just in the present does that sound about right?

[0:25:33]

Male speaker: Yes cool.

Jackie: Yes.

Mathew: So this was kind of some of my thoughts I was having you know in that even and they were about magic and they kind of revolved actually around Paleolithic cave painting strangely enough. So I’ll go ahead now, this is what I wrote its called notes towards a sympathetic image.

So from the first of these principles namely the love of similarity, the magician infers that she can produce any effect she desires merely by imitating it. From the second she infers that whatever she does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact whether it formed part of her body or not. What of the image, of its completeness on the one hand and its lack of result on the other? What of the cartographic inversion, the math that becomes the territory? What of this extensively debates type of reality? Of this crude and spectacular relations, the product of a world mediated by false images. What of an epistemic order built upon the close binary of the ideal and its representation? What of this reality and what of the world shot through with truth? What of movement, of time, incompleteness, of non-knowledge and unresolved?

Fragments then for movement, for contradiction, for an incomplete and sympathetic image, fragments then for the two principles of magic, homeopathy and cotangent where like produces like and the properties of one are transferred to the other by way of intimate contact. This illogic’s or “mistakes” of an erroneous system are internal event and fundamentally contaminated, nothing more than a primitive misapplication of concepts, of similarity and continuity. Fragments then or both principles of magic they assume that things act on each other at a distance through a secret sympathy, the impulse being transmitted from one to the other by means of what we may conceive as a kind of invisible ether.

The object in the image both shot through with their distance, a special temporal sympathy across the territory and across the map. To get a hold of something at a great distance, to stand in the radiance of an erratic presence, that flash of history in a moment of danger, the force propelling you backward yet somehow forward, parallax within a dialectical movement. And this magic objects are simultaneously viewed with exhibition value and co-value, a sign value and symbolic value. But when shattered the fragments open up and become available.

The anthropological theorization if prehistoric paintings suggest that these images operated at the level of consecration, performative images they brought forth into the world the action they depicted. That is to say they were of the thing itself, a register, a valiance of the thing distributed across distance and time [0:29:01] [indiscernible] varying speeds and varying in forms, produced by and producing reality. The great rift between representation and our deal, the distance between the not knowing of this illogical and irrational operations and the knowing or logical and rational is broken down.

The logic of the performative image is that it is part and parcel of the thing, that it is invoked and extended toward us in time through its image. Partial views, fleeting moments, embodied perspectives, parallax, self evidence, erratic, messianic or magical power, affectivity, textures, temporalities, economies of circulation, modes of reception are here brought forth into the world.

Doing away with antilogies and the concept of original only arises after the original is multiplied. The thing is resident and multivalent, not the imperfect and profane manifestation of the ideal but a side of presence, of none knowledge against the appearance of every surface and every curvature of line at the edge of every frame of vast and empty field and ones terrifying and it’s a [0:30:24] [indiscernible] of uncertainty and yet accelerating as we fall. For just as we know that the product of knowledge truth and power are intimately linked, we must also acknowledge the productive of none knowledge to create that rapture within linear or historical time. That blasting from the continuum of history and power and great account of mystification the specific fragility of the present and its secrets sympathies.

[0:30:58]

Jackie: Nice yeah.

Male speaker: That’s very good thank you, thank you so much.

Male speaker: Sure I guess that’s a some kind of cocaine is in order. But yeah so that’s sort of that’s what I wrote in response to what happened in Paris.

Jackie: Yeah well I’m very it’s you know there is a lot of things I mean you’ve obviously you know may give even more much more thought for and sophisticated reading of the event. But yeah there is a lot of things in it for me that you know I have thought about after making that event. and a way that it unfolded and there was so many people involved and there was so much generosity between everyone to really make it work and yet it was with the a fragmented like the people who were in the event did really know what the other people were doing. So there was a level of there was level of trust, there was a level of waiting to see what the performance before yours to see if you wanted to adapt yours a little bit to what was going on and you’ve really encapsulated a very nice and a big explanation and description of what was happening there.

Male speaker: Thanks so much.

Male Speaker: I think maybe a lot of it had to do yeah with the fact that I was performing for a lot of it, and so there was this kind of - I was well mostly actually aware of kind of having an embodied experience more than I typically I’m you know. and that’s something I have been thinking about a lot lately is this sort of I don’t know maybe it’s my own like lifestyle because I’m not like going to the gym or anything but this idea of like you know the uncertainty of the body or something as well it’s kind of counter point to kind of analogies of the image [0:33:37] [inaudible] the vision or something like that.

Jackie: Yeah.

Male speaker: Okay well let’s see a couple of [0:33:47] [indiscernible] its, he doesn’t understand anything. So would you like to proceed with something? Just before I say I have just received an email from the people in Melbourne which I haven’t read to say that they’ve sent us a telepathic message and if I hope it will, it all kind of say what it is so maybe at some point you could maybe take a bit of time to see if anyone is able to receive the telepathic message.

Male speaker: Jeff are they sending to anyone particular or just for the generally [0:34:20] [cross talk]

Male speaker: They are sending to this group yeah. Steve was saying that he’s been sending, I have explained the best I could what is screw it was and how they were kind of constituted or whatever and I said that could use the same to them but and so maybe how did you want to send us something or say anything or…?

Male speaker: Not really just.

Male speaker: Because you just said that you didn’t understand a lot of that and so I just thought it could be interesting you know.

Male speaker: Yeah well I think I don’t have to understand everything just that I’m fine I’m happy to you know to try to figure out what’s going on now and how my task of you know have a lead of it understanding about what’s going on but probably its wrong.

[0:35:21]

Jackie: Jeffery well what I was it just occurred to me that perhaps we could say a little bit more about that event because Mathew’s text has a made a response to the event but I don’t think were really given a description of it.

Male speaker: Yeah I’m sure that you know it was a great sort of event something that like I said and it needs more well scrutiny to kind of understand that takes part that respond to what happened that we don’t have in common but yeah sure tell a bit about the event sure.

Jackie: Well we made an event in Paris a couple of weeks ago for the [0:36:06] [indiscernible] and we called it speak easy medicine show and Jeffery did mention a few things about it a bit earlier in the conversation but we invited about 25 people to be involved in the event. And that as Jeffery said we had someone who had made this Morse code to the, as a sound work and we had people giving rating making ratings. We had singing we had speakers we had someone who made an [0:36:45] [indiscernible] for the audience to drink, we had a novelist Denis Fukard [phonetic] [0:36:51] from Paris who adopted one of his novels into a very short play.

And the whole idea of this event was to bring people together to speak and we have been thinking a lot before more before this event that also in our work for some time now we’ve been thinking a lot about speech and perhaps the impossibility of speech what can we talk about now and who do we speak to when we want to speak, is it possible to speak about politics, is it possible to speak about social issues. And you know I think that certainly the way that I feel more and more is that there is not there is either a desire for people not to speak to each other in these particular kinds of ways. So what we look for is a way of bringing people together and speaking. So we don’t in this situation we don’t invite people to speak about anything in particular but we just ask them if they would like to speak and if they have something to say. So this event run over just down to two hours and people spoke saying and you know [0:38:12] [indiscernible] all sorts of things. And so Matthew’s text is really a response to the event on that day it was a response to the speakings in Madison show event. Jeffery is there anything that you could add to that?

Jeffrey: No look I suppose I am just thinking along the lines where we are just trying to show that there is on the one hand that Matthew’s was a very detailed and considered kind of thing and then someone else said I would like to have some cocaine now would you understand immediately. and so we are just kind of got continuing to kind of build a field of all of these different ways of talking together and we are grasping some of it and we are not getting other bits and then in Hal’s case there is problem with the language like we had been friends we haven’t really learned French very well you know there is a lot of things that we just don’t kind of get like that.

So we’ve sort of tried to be open to that and it seems what we are doing with this experiment if you want to call of that tonight to believe some of these things floating without feeling I have to be, I suppose what I’m trying to say is that if they are not closed off and obviously consumed, it doesn’t mean they don’t exist. So that if Matthew [0:39:34] [indiscernible] then we didn’t get the whole thing that it doesn’t mean it’s kind of not there it’s still there in some kind of way and we are aware that it’s there even if we haven’t you know consumed or understood it all in that kind of way. I was just wondering if I could invite everyone like if we could just take a couple of minutes and like I’m getting its ten plus four here so its ten plus if you are at? Some is calling.

Male speaker: Hello.

Male Speaker: No I am just adding someone else to the call.

Male speaker: Yeah to take let’s say two minutes to receive this telepathic message for Melbourne and to write onto the Skype chat thing if you’ve got anything at all.

Jackie: Yeah I think it’s probably maybe it’s what we could do is just decide you know just to have two minutes of silence so we can attempt to receive something.

Male speaker: Yeah is that seemed okay is anyone?

Jackie: Someone got Jeffery do have got a timer?

Male speaker: Yeah I have a timer here we can do this.

Male speaker: Maybe you can do it and it would be great the thing is like I think it was Mathew before sort of or someone said that it’s not so much that we believe in telepathy we are just kind of working on this as some kind of material case about the whole thing. Go ahead all right lets receive the message okay Scott lets would you want to go for two minutes and see how we go?

Scott: Sure starting now. That’s the timer.

Male speaker: All right if you’ve got anything to write and need so probably its time I don’t know.

Jackie: Got a cube in a black way.

Male speaker: Is that Alyssa I mean are you asking that question? Yes of course. It’s out there in Melbourne. They are sending it in Melbourne and what we found it doesn’t necessarily come on straight away and then other times you get complete everything send really really unrelated and then sometimes of course you may need subtract your time you know like something that you couldn’t see in relation to twitter the connection develops over time you know kind of I guess strange but predictable way like that.

Male speaker: So will your friends in Melbourne…

Jackie: So what if they yeah what if they?

Male speaker: Well is anyone else going to come in with anymore before I tell you? Has anyone got?

Jackie: Mathieu Raner what did you get?

Male speaker: I got the word dolphin.

Jackie: Is that and [0:45:26] [indiscernible] see Mathieu that Mathieu saw the word bullet, why are you…?

Male speaker: Well dolphin. Anyone else got anything there?

Jackie: Did anyone else think that they received a message?

Male speaker: Because I will open it and open have a look because I mean ones we’ve looked it’s kind of done you know.

Male speaker: I just got a little heart burn and anxiety that’s it.

Male speaker: Yeah well.

Jackie: And Pat got something red yeah?

Male speaker: Well I have got these nonsense words which I have never heard before you know.

Jackie: Oh okay someone got a beach yeah.

Male speaker: We will open it up then.

Jackie: Its Marie, we’ve got [0:46:21] [indiscernible] got here?

Male speaker: No I don’t think so I don’t think so.

Male speaker: I think she and Kiera both went offline.

Jackie: Right.

Male speaker: Steven did you get anything? Oh he is gone is he?

Stephen: No I’m here I’m afraid I didn’t I don’t know I don’t really know.

Male speaker: That’s cool like.

Male speaker: I don’t know what I got right?

Male speaker: Very good okay I’m going to open it.

Jackie: Okay let’s hear what it was.

Male speaker: Attached is the image that Sean and I are trying to send telepathy to Melbourne to basekamp. We send it from 6:00 to 6:30 Philadelphia time other things that might have got send along with include the kitchen Veronica was in, she was in she send at the school assembling Sean was in while he send so [0:47:23] [inaudible]

Jackie: Okay so they are in two different places when they send the message?

Male speaker: Yeah. Just opening in Photoshop here. And so can I attach this image and send it to everyone without saying what it is? How do I do that Scott?

Male speaker: Is it a jpeg?

Male speaker: Yes it is a jpeg.

Male speaker: I think you can just drag it yeah.

Jackie: You just do a same file and attach it.

Male speaker: I will just put it on the desktop just to see.

Jackie: And then I guess everyone has to accept it.

Male speaker: Sort of just taking a second if you want to go on and do something else you should probably go I allow you.

Jackie: Anymore questions from anyone that might kind of take us in a direction?

Male speaker: So when do I get to share?

Jackie: No you go in same file so [0:48:26] [indiscernible] can you see the same file button?

Male speaker: Sorry I’m stupid.

Jackie: Just on top of the window it’s got add, topic, hang you know and it should have same file.

Male speaker: So you know I don’t see that I get a there is a more button on mine that drops down and you can choose same file from there.

Male speaker: More okay send file okay I’m on it here it comes.

Male speaker: Receiving. This is a kind of telepathy.

Male speaker: Yeah, exactly eccentric yes to me that makes sense. Because it’s sort of like a knowledge that what we don’t know it’s not anymore and masturbation would be common knowledge. What is that picture, I still haven’t seen it?

Jackie: Well it’s a painting of a woman who looks like some 17th century man. But it’s sort of funny it’s got a little bit of the Van Gogh about it. You should be able to save in the email Jeffery email. Yeah well I didn’t see anyone I didn’t see anyone wearing a purple shirt.

[0:50:19]

Male speaker: Okay alright I got it. So could we get anything anything whatsoever?

Jackie: Well no dolphins or swans.

Male speaker: Telepathy is like a language, Patrick I don’t know who you are but yeah well that’s a really or does it become language ones we I don’t know use it or talk about it in some case. This is just what we found was really interesting it’s kind of doing it with no expectations and it being open to its failures it leads you to all these kind of ulterior places and stuff that especially how you can time might become quite interesting. Because you weren’t looking to see anything more implied than anything than what we actually got. But of course when you look at this now well nothing familiar comes what we got if it’s a swan or a beach or whatever comes.

Male speaker: So if the images that came into people’s mind weren’t what we are sending in the telepathic message is does it is it a mistake?

Male speaker: Well what we’ve originally started thinking of was like kind of lost mail office you know. that suddenly went useless in that you know and the images definitely say something about us individually and its [0:51:59] [indiscernible] what we attributed and but I don’t know I don’t really know how to articulate it but then we have found this through time things do attach in a way that they seem completely fragmented and unattached to what’s going on but that’s how it seems to me now you know. It sort of seems like failure.

The other thing that really got involved in which is the idea if we did or think it will kind of be horrifying and maybe a bit [0:52:33] [indiscernible] you know. like if we all saw a beach and then we got a beach like it will sort of be horrifying likely but in a way we are quite open to it invoke in something like I don’t know more I don’t know is it more in the possibly because I’m not quite sure about it [0:52:53] [indiscernible] with my ability to articulate yeah what’s interesting.

Jackie: I may have to say that our telepathic experiments have not been terrible successful.

Male speaker: [0:53:06] [indiscernible]

Jackie: Yeah so but we you know but we are in a sense we are in the middle of a research about telepathy so we continue to make things telepathic classes or receptions.

Male speaker: I was just thinking about your error deceit mistakes publication and that you know it wasn’t really that long ago we were talking with the errorists and about ideas of success and error, mistakes and all that and that’s definitely not foreign territory for you guys. I was curious you know that I think you embrace experiments not knowing well and like you said because yeah I think not just as a kind of foil disguise like fear of things not going well or possible but because that’s something that you genuinely - another area that’s been a big part of your work and not just part of your work but part of the frame works that you’ve helped setup which is really I think what we are mostly interested in. so I mean even in a class like this it’s a kind of frame work you know methodologies even or approaches are for me I think I wonder you know sometimes I wonder what the value of talking about things that people are doing or the experiments people are getting out there and maybe describing [0:54:53] [indiscernible] what the value of that is you know and.-

Male speaker: Describing the most what?

Male speaker: As art worlds or even micro art worlds especially for creative practices or things that people do that often get distorted by placing back into a kind of framework that you know that either displays or supports or even understands those works or these processes as a kind of protocol art.

[0:55:24]

Male speaker: Well presumably sorry.

Male speaker: No no I guess what I meant was just that I think much of what you guys have done at least in my impression knowing you over like over a long period of time is that you are really interested in certain question but just not sort of not only illustrating them with your work as artists where you make art objects that then get sorted into a certain kind of framework which of course they do. Because you do have a foot in world that would be considered you know I mean that are would be mainstream our world so do many of us. But that you at the same time uncompromisingly you setup these kinds of situations where they just can’t easily be understood or reconciled with those world and that not you, you are not just trying to disintegrate then you are actively developing your own and I’m really excited about interested in that.

Male speaker: Well I think too though it’s very concurrent is what you know this idea of plausible art will do something because I’m guessing here but presumably [0:56:30] [indiscernible] in which they had nothing in there whereas now ones [0:56:35] [indiscernible] got talked about it, it has incredible urgency and you know it might even stupid balance sort of thing. so you know this idea of making speak and discussion around something or to identify that something plausible is kind of you know well it’s not an interesting it’s kind of seems that’s really necessary sort of thing to [0:57:03] [inaudible]

Jackie: Well maybe in a sense what we are seeking is to know more and I think with the errors and then sits mistakes project that what I think is that we only know ourselves through mistakes and deceits. And so thinking about it in that way it was a research to bring together some way of understanding something. and so when we invited people to be involved people to be involved in that project you know what we would ask them was not to do a lot of work because we don’t really like giving people a lot of work to do and making them come up with new ideas. So we would write to people and say we are working on this project it’s about errors, deceits and mistakes. If you have something in your computer or something that you’ve been thinking about recently, maybe you would like to send it to us to include in the publication.

And then in the sense the project becomes performaty. so in a way it’s not a publication anymore its becomes a kind of confirmative act that we are the first audience for and I think we anticipate that other people then will be the audience for these acts that then play themselves out on the paper. And it seems to me you know the way we’ve been speaking tonight this whole idea of not knowing is really to bring people together so that we know more.

Male speaker: Well exactly it’s not a sort of fetishzing of a lack of understanding or something like that.

Jackie: No not at all. Because in fact when you bring you know we’ve talked about this when you bring a group of people together they really know a lot they know different things.

Male speaker: Yeah and not knowing can be used like you know in the case of global warming and things like that you know it’s the things that aren’t in doubt have been thrown into doubt in a really ugly way using as part of post modern strategies of not knowing in a really kind of disingenuous way. and so you know I don’t think that we could you know just sort of stay not knowing this you know an ethic place with what you don’t know good things will necessary follow but it was more to you know to realize that what we are working with is not such a big part of the picture.

Male Speaker: Are you saying then that so that knowing actually remains your horizon, not knowing is simply the way that dominant expert culture has characterized people who are not legitimized as knowledgeable and so you bring people together who are not like indexed within the knowledge economy, you bring them together and you find out that they have more knowledge than the expert culture was prepared to acknowledge, is that right?

Male Speaker: Yeah and that, I mean what you are touching on there is potentially political in a way that I really like the idea of the two but you know not in the [1:00:57] [indiscernible] not in a predestined way but maybe in a use way, the people are using more stuff together but it’s just not picturing sort of thing. So people could actually be together more than what they are aware rather than this kind of fantasy of having the notion and individualism. Like it’s hard to know how real [1:01:20] [indiscernible] or something.

Male Speaker: And just, Mathew hi.

Male Speaker: Hi Mathew.

Male Speaker: But I think that hits on you know the song that you performed, the – I don’t know of the title…

Male Speaker: The one that ends up the show, yeah.

Male Speaker: But I mean I think that the lyrics are really or when you sort of demand and you are sort of narrating the story about reading your email over and then you say like you know, let me show you what my use value is kind of thing. I mean I think that that kind of hits on it in a good way. I don’t know if you have those lyrics that you can share.

Male Speaker: I don’t know if I can find that, let me just see. It was actually, it’s what I got from a book by [1:02:13] [indiscernible] wrote here as Francis Ferguson that was arguing that pornography was kind of useful [1:02:24] [inaudible] someone just joined us.

Male Speaker: Yes, someone we threw out the [1:02:33] [inaudible] probably adding people like I dropped or maybe out of the field.

Male Speaker: Okay I’ve got a rough version where I can put this on? You are starting to cover a lot of ground and so I am sorry if it’s too much.

Male Speaker: This is the song?

Male Speaker: Yeah. So it was really a way of trying like I read a book so you know like to put this in a more series seems like we are in a more kind of readable way than what we’ve been talking so far. I remember reading a book, ‘The Summer before Last’ and being you know just totally you know having compelling feelings about this book that had all these relevance to me. but if you hadn’t asked me to explain the book to you, it was – you know I had no [1:03:24] [indiscernible] at all just sort of say, well it’s about using, it’s about that and to tell you what it was, you know to bring it into any coherent shape. And then after about a year and a half, I kind of got this idea about what she was talking about, his use value that you know you [1:03:42] [indiscernible] sense that if it wasn’t so much that we were kind of in a kind of bad use value but the way that it was possible for someone to reveal [1:03:56] [indiscernible] family and I can’t really explain better than that.

And there was something about what she was saying that’s very explicit and pornographic themes are playing the role of that in our society that rather than us being you know desecrated by our use value or used up by [1:04:22] [indiscernible] but it was prompt in an opportunity to kind of show something new and revelatory about a physical and kind of mental selves or something. And so far one of the reviews of this book by Francis Ferguson went on to kind of say that she thought that what pornography could teach religion because if you think about [1:04:44] [indiscernible] needs ecstasy of the virgin and that religion has a lot of kind of pornographic revelatory you know beyond knowledge kind of moments like that that now Christianity has moved into a very kind of damn sort of knowing where all its about its about us keeping things as they are.

[1:05:07]

Whereas religion used to have a kind of very sexual revelatory kind of orgasmic kind of quality about it and so this was what this book was talking about here, the ideal.

Male Speaker: But Jeff aren’t you really just talking about two forms of expert culture, disagreeing about what the relevant point of debates are? I mean someone who is an expert on pornography and someone who is an expert on theology will not agree, but there are two experts that are disagreeing and we know that kind of situation. I think, I mean I think that I misunderstood what you guys were on about. I think I didn’t understand your point. I thought that you were talking about not knowing per se. In other words not knowing as a form of knowledge. And that’s much more radical because that is a form which is excluded from the epistemology per se, you see what I mean?

Male Speaker: Yeah I mean I actually had a talk the other night and someone said I don’t exactly get what you are saying and forgive me but I don’t either. You know that’s its more to do as most speaking of the straits of things and sure there are things that become more clear over time. But what the distinction you are making between not knowledge and experts going over particular issues, is that what you meant? Making a distinction between those two things or…?

Male Speaker: Well I think that generally speaking you know debates between, almost all legitimate debates have been two different kinds of expert culture. In other words if you can talk the talk and you have the legitimacy of your community, you can go and challenge another expert. But there is a kind of knowledge that all experts will exclude as non knowledge. I don’t know whether it’s just I mean sometimes we think of that as – you were talking about user ship, I mean users are people who are considered so stupid that they [1:07:25] [inaudible] thing that the expert come up with before them. But that’s not the same thing as pornography, I mean there are specialists on pornography, I mean obviously people who produce pornography and are involved in pornography know a lot about pornography.

Of course it could be dismissed as being stupid by people who are experts on theology. But that doesn’t change the fact that there are people that are speaking with legitimacy of the accumulated knowledge of their fields. What’s interesting though is what psychoanalyst call space of non knowledge or non-knowing or not knowing is where, is speaking from a position which is validated by nothing and by no one. And that’s where the hidden, and I mean it’s not even hidden because it’s not even unmainable kind of space from which knowledge or anything with, while may ever emerge.

Male Speaker: Sure.

Male Speaker: I mean in terms of psychoanalysis that’s where you don’t usually understand yourself like and it gets bigger the more you try and do it and you know generally the role of, one of the role of psychoanalysis is just to find a way, to find acceptable rhymes through where you are in the midst of all this non knowledge or communical of minds.

Male Speaker: Exactly and I totally agree with that. Can I extend that maybe in a banal direction? Because one of the questions that I wanted to ask you right from the beginning is why you chose the name ‘A Constructed World?’

Male Speaker: This isn’t [1:09:25] [cross talk]

Male Speaker: But its – hang on my question maybe is not every interesting either but it wants to be interesting because if we are working with things that are, if we are working with a space of not knowing, it’s very difficult to construct anything. And at the same time, there is a kind of a parallel with the fact that everybody who lives in the world and operates in one, kind of goes along with the idea that that world is not a construct. Because if you start thinking of the world is constructed, it becomes like fake and you can’t really accept it anymore. So we kind of I don’t know rule out that possibility. It’s not just by now to say the world is a constructed world; it’s true by definition but somehow always radical. How do you like square that circle?

Male Speaker: Well my version of it and because its changed a lot like once yourself something, it takes, and its seven down years, so you know it’s taken on a lot of – the way that I was thinking about it and I suppose to something, that it’s something that is put together rather than procedural and maybe put together as we are doing something like that. Or you know like it was just a way to find way of talking about something that didn’t have an origin and something that wasn’t you know implicitly there that you can find that sort of thing, well that – and that it is something that could be put together or made up or continued to be put together or made up as you kind of interacted with something like that.

Jackie: In a way it’s a little bit of a mistake that we’ve ended up with this name I think.

Male Speaker: What do you mean Jackie?

Jackie: Well I mean it was a name that we used in a few projects very early on and then we had a constructible publishing which was found in a magazine. And so we just kept using the name and the different times we did think you know perhaps we should change our name, you know change our artistic way and the thing was that we’ve done so many projects using that name but we had you know we just thought that it was more of a continuum to keep using it. At one point we did change our name to costructed world and that was kind of a mistake as well that it could be.

Male Speaker: So when we mistakenly wrote that in a catalogue and it was printed goes back well, and so for about six months we tried to change prospected like in abstract and the costructed and so we tried to change our name and [1:12:35] [indiscernible] was so [1:12:36] [indiscernible] we are just sort of, it was yeah there it is.

Jackie: People kept running to us and say do you realize that you’ve misspelled your name…

Male Speaker: And they wore us down. So we made it work about it, we did make it work about that prospect. But I suppose you know that’s the sort of – and then apparently in the like 2000s Constructed World had some various specific meaning in terms of video games and how video games are put together. If you look up in wiki and things like that, that it was there and that came kind of after in our knowledge at least, in our Wiki that came after kind of using, and then it’s used economically as well. So I guess it is something that – we didn’t have a manifesto, let’s put it that way, like we didn’t have an origin including that, it’s not as you can know.

Male Speaker: You know this did come up earlier and I wouldn’t want to kind of derail but I think it’s kind of important right? That you’ve – we’ve been talking a bit about psychoanalysis but also probably an equal measure Constructed World, I mean your backgrounds draws, well I don’t know if its equal measure but draw from Rock and Roll in my understanding almost doesn’t, not as much as from psychoanalysis.

Male Speaker: You mean that kind of origins and…

Male Speaker: Yeah origins and competencies and also things from other, ideas from other fields that you draw from in your work.

Male Speaker: Well I think we just wanted to be where more people were and you know the art world can be as we all know, I think everyone on this, discussion it can be pretty [1:14:41] [indiscernible] specific so you know we were just interested in having defined ways which involve big pool, getting into a conversation with some more people. And you know like I suppose in psychoanalysis and rock roll and things like that this could potentially lead other people there that their urges and new pulses might overlap and that they might see themselves participators you know where the gap between the sending or receiving or production and reception starts to become a bit more interesting rather than being [1:15:26] [indiscernible] out someone knowing and someone else not knowing.

[1:15:29]

Male Speaker: Right yeah, I mean you’ve been in so many group situation now. I mean I am aware of a couple of handfuls of them and I am sure there is a lot more that you’ve got that I don’t know about. You know and what I am really interested in, I mean one of the many things but one in particular is how these experiments where people enter a space not knowing together, I mean that’s one of your primary strategies for a long time. The kind of knowledge that’s costructive there, how does that sort of spin back out into other sort of rebuild other world structures? Because when you group together in a group, you create a kind of world, a micro world, you know, a temporary one off and some of them have been ongoing projects like the Dump Collector and other group situations that have kind of like an organism people have come in and out of, it’s taken on this life that has kept going. But another case is that they are not quite sure but I think in all cases you are, there is an experiment, part of what you get from an experiment is you, you are not necessarily only focused on results but I think you really want to learn something about groups and I guess I am curious, what if those things, not necessarily just that it filter through your understanding but maybe that too but at least in your awareness have kind of filtered their way out into the world and kind of…

Male Speaker: I think the primary level but we’ve been very happy if people wanted to do stuff together and that’s been really important to us. But we have had groups that have started working, we stayed together 10 years and even more and that has happened quite a few times. So if people wanted to somehow it seems important especially after we Mind of Vegan left the place of working like that. But I think what is touching on for me now is what we are talking about in this group now is a real interest to me but Jackie and I are aware that it generated so much information and in a way we’ve not drawn that much I don’t know you couldn’t really call it understanding but we haven’t really drawn that much already information from what was started and that we really want to begin to concentrate on that more to kind of even if it’s very complicated to work with more people to go over.

Like if you think of what we’ve just done tonight, you know like if you look at one of this telepathy experiments, it’s in fact very complex in itself and we’ve kind of being going on and on and on generating all of these things and I guess it’s about time in having worked together for so long and even our age to think about now how could we perhaps make more analysis and of what we’ve kind of done each time and to take that more serious rather than just trying to create the next thing to perhaps give it some sort of place and a kind of field of knowledge maybe or something.

Jackie: But the moment we are working with a group of people on a project that’s called [1:18:59] [indiscernible] archive and Mathew Raner is involved in that group. There are about 10 people involved in it and it’s a group of professional and emerging artists, art, historian, curators and we meet and really starting with this idea of speech and what can you say what is it possible to say, we are making research. And so this group is just involved in being together and getting to know each other and so we are at the point where I hope we are just about to take off to make some work together. And the thing for me that’s very interesting is that even thought I have had a lot of experience working in groups, with groups of people, it’s still difficult to work with other people.

[1:19:58]

And so there is something very interesting in understanding myself in the group and being with other people and negotiating how I can be an individual in the group and how I can be a participant and how I can put something in and get something out at the same time. So that group is emotion at the moment.

Male Speaker: Just in terms of the sidekicks that are going on while we’ve been talking on just sort of glancing over it, I am not comprehending it in any way at all. But one of the things that’s changed for us that we still – we used to find the relation with other people in the sense that they would say that if someone else said I don’t know about art, we would decide that that was [1:20:48] [indiscernible] not that we said that they did not or that the institution said that they didn’t not but the persons themselves would decide that they did not know about art, that this was in a sense a useful subcategory or category for us to work with. And we kind of worked with that for a long time.

But now with the kind of changing technology and stuff that we are getting a different kind of scene now that everything has been deregulated so much that I remember going to the fiack [1:21:18] [phonetic], the art fair and seeing a really kind of imminent curator there looking at a show and I said to him what do you think about all these? And she said, “I am meant to be an expert but I don’t even know any of the artist.” So that you are getting another kind of deregulation from within when no one could keep up with all of the information that is going on and given that we are all or many of us now are so educated like I was talking about the remote control TV visually in other words, but you can’t really be outside of knowledge in the world. You know this is impossible.

So I don’t know, it’s sort of interesting like to keep the how we could on make on map these changing thing that the experts don’t know and there is no one in one way you can’t really have a place that knows nothing about – now I don’t know if you’ve all noticed but there are all these examples in that were dominant [1:22:20] [indiscernible] talking about performance side and they are like Lady Gaga and Walkin Phoenix and there have been all these examples now where they go, got performance art whereas for a long time, performance art was seeing as something that was very marginal crooked and now as this kind of rigid steady place in the mass main stream sort of thing. And so I think that these changes are really interesting too.

Male Speaker: Absolutely and you know and Jeff I know we’ve had a few chats briefly with them and I have I guess a wide spread clear understandings of collective creating, creativity have been changing, I think relates to a lot of what you are talking about because you are talking about technology but it’s also generational. Number two, impact one another. There is some of the generation predictors as Lee here often talks to us about. Looks at group activities in the changing phase of not just what people do together but what they understand themselves within groups seems to be changing. I mean that’s something I think that will be really worth talking together about more over time.

Male Speaker: Yeah well it’s just mate like a lot of – there are so many dubious things obviously with technology and fantasism and fakes and you know especially about socialiabilty and you know I think people are very part of, aware of this and there are so many things that we already did before the technology that haven’t really changed in other ways too. But so…

Male Speaker: Yeah absolutely, some description of this, not that technology is changing so much but that technology is just amplifying the kind of social networks that we already have. You know this idea of somehow a free and open web or the social web would give us new freedoms and new possibilities but at some studies, referring to studies generically is a really good way to try to [1:24:56] [indiscernible] someone says so, sorry about that saying that but I thinking of something in particular but I can’t recall it now well but I looked at Facebook as a sort of mirror of the type of [1:25:14] [indiscernible] exist, it already existed in our culture.

And not just that application but others where it’s not so much that these are opening up new possibilities, of course they are in a way but in another way they are really just emphasizing and amplifying the kinds of inequalities that we already have, the kind of cliques that we have already formed, you know the lines of thinking that we already follow, excluding and other that we already do in order to form a group and things like that.

[1:25:49]

I am definitely not being fatalist by mentioning that, I am just saying that I think we need to do more of what you guys are doing and a sense of going in a group situation you are not just going into it, you are also helping them to set up but you also go into the ones that other people set up and you are trying to like get a sense of what they are what they could be, your green knowledge that you have but you are also interested in other claims of knowledge that other people have and not just a certain idea of what knowledge is. That’s not an expert idea but with the assumption the kind of interesting assumption that you take that everybody has knowledge, different forms of knowledge and that we can collectively come up with something else and I am really interested in that because a lot of what you are – you know Steven is still here. Great!

A lot of what you are doing or a lot of what I am seeing come out of it, there is something to it and that you kind of have to, we can’t really cover it all up in two hours of course. We’ve got to look at each project or each experience one at a time and rally get a sense of what can come out of it. But I would love it if there are other more opportunities for you to share that stuff, you know or for us to distill some of that so that we can learn from what you’ve learnt too.

Male Speaker: Well I am going to have to go because I am actually going to teach a class here at the school where I am…

Male Speaker: No that’s all right.

Male Speaker: But you know I’ve got really a lot out of it tonight and I think it is interesting so if we could do it sooner than the last time. I don’t know like it’s really fantastic every wake just seeing that you continue to this discussion and I think it’s kind of amazing.

Male Speaker: Yeah and you’ve even expanded the space at basekamp for the next several months with Atoine Mathew which was great.

Jackie: Well I mean that would be great if they were open to do something at basekamp and you know work with a lot of people or do something with you that reflects something like this.

Male Speaker: Well we are talking about it, we’ve got into some discussions and it would be great to continue to connect with you guys on that.

Jackie: Yeah, yeah.

Male Speaker: You should.

Male Speaker: Cool well guys thank you so much for coming and thanks everyone for…

Male Speaker: Well thanks everyone else for coming too. Of course there is a whole of stuff that you [1:28:23] [indiscernible]

Jackie: I am sorry I couldn’t, I just couldn’t really follow the text because I was trying to listen to what like we were saying, like what was happening within the audio.

Male Speaker: It’s a strange space to sort of juggle this too at the same time.

Jackie: Well it’s really very interesting because in fact you know there is this kind of subgroup thing going on within this group. People are having conversation with each other and other people coming into those written conversation. So it’s quite interesting, there is quite a lot happening in a parallel space and I don't know in some ways you know some of, we’ve missed some of this really interesting things that have come up in the text.

Male Speaker: Its very interesting and it’s not lots there is a model too, you know that it’s kind of all still there, I mean that’s all written down and what Sean and Veronica can give you, they are perfectly willing to go over it again and go back and that’s presented they did not understood trying to [1:29:32] [indiscernible]. So I am thinking that that, you know this is what we’ve got [1:29:36] [indiscernible] and I hope as a magazine the expert, it’s really just been a time of doing something of wanting to perhaps I don’t know analyze and grasp things a bit more rather than just keep making something new and something.

[1:29:56]

Jackie: Look I think really the think for us, the reason why we work in this way is that we want to be in contact with more people and it’s not really to make a research about groups and we certainly aren’t making research about not knowing. I mean not knowing is a very – I mean I think in a way we’ve over talked about it because I mean of course the thing we know is that knowledge is small and what we do know that what we could not know. So we have an interest but if we don’t know because what we know is so minuet, what is that we have together and what is it the knowledge that we can have between us we can share.

So you know it’s a kind of contradictory field in the way that we use it. But the thing we are really interested in is making conversation and attempting to make contact through conversation and to get something out of it. You know to make us feel good, to make other people feel good and to feel like we are in contact and we are not alone.

Male Speaker: Well we are actually end of the [1:31:10] [cross talk]

Male Speaker: Thanks very much guys and…

Male Speaker: Thank you.

Jackie: And hope to talk to you all again soon. Bye.

Male Speaker: Bye.

Male Speaker: Bye.

Male Speaker: Bye everyone, have a great evening and morning and afternoon. Closing music anyone? Can you sing us a song? Okay.

Child Speaking: [1:31:47] [inaudible] get in the spaceship dad. I have a fun dad like [1:32:07] [inaudible] [singing]

[1:34:07] End of Audio

Week 32: E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology)

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is another event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

This week we’ll be talking with Julie Martin, one of the founders — with artist Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver, then a research scientist at Bell Laboratories — of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), a groundbreaking initiative in the late 1960s that brought artists, engineers and scientists together in an attempt to rethink and to overcome the split between the worlds of art, science and technology that had come to characterize and warp modernity.

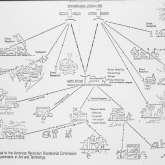

A series of performances organized in 1966 incorporating video projection, wireless sound transmission, and Doppler sonar — now commonplace but at the time emergent technologies, still untried in art production — laid the way for the group’s founding in 1967. Until the early 1980s (and the beginning of the Reagan era), E.A.T. promoted interdisciplinary collaborations through a program pairing artists and engineers. It also encouraged research into new means of expression at the crossroads of art and such emerging technologies as computer-generated images and sounds, satellite transmission, synthetic materials and robotics.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Experiments_in_Art_and_Technology

http://www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/page.php?NumPage=237

The whole experiment, with all its utopian energy, is somehow reminiscent of a Thomas Pynchon novel: born of a union between the anything-is-plausible outlook typical of art and science at the time and the blossoming technology industries indirectly funded by the Vietnam war, E.A.T. is undoubtedly one of the most inspiring and emblematic attempts ever undertaken to bridge the gap between the worlds of art and technique. As instructive in its measurable success as in its ultimate inability to correct for the ideological bias inherent to an industrial laboratory, E.A.T. continues to point to a horizon shared by many collectives today — as for instance in its 1969 call for PROJECTS OUTSIDE ART, dealing with such issues as “education, health, housing, concern for the natural environment, climate control, transportation, energy production and distribution, communication, food production and distribution, women’s environment, cooking entertainment, sports…”

Transcription

Week 32: E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology)

[0:00:00]

Male speaker: Well hey everybody.

Scott: Hi guys. Oh one thing I forgot to mention everybody if you do want to speak I mean feel free but just so that we record this just for this publication that we are putting up next year so if you don’t mind we will just pass the mic around and we will just deal with that formality just so we can have something about that. But hey everybody that’s there if anybody if you see anybody getting drop can you just let me know because I’m going to be kind of going back and forth between here and talking. So Steven can you hear me?

Steven: I can here you great Scott hi Julie.

Julie: Hi.

Scott: Well let me just give a super quick intro. So hi for everybody tats out there we just kind of you know we took our time getting started because we didn’t want to be too early you know we didn’t want to set the bar too high for next week. So for anyone out there who doesn’t come to this normally just pay attention just check out the Skype chart and if you know you feel free to speak up if you want to there is a little message up at the top about that and if you would rather just take you’re your time to type out what you want to say or ask go ahead and do that we will queue up questions or whenever they seem appropriate or whenever you want to jump in.

So yeah so this week we are following in our series this year of looking at another example of A Plausible Art Worlds each and we are pleased to have Julie martin with us who’s representing experiments in art and technology the 40 some year projecting that were looking at a kind of a prototype in its realm I guess you can say or that’s spear headed a lot of other projects who have sense in her curly following some of the strategies and were really interested in seeing this as a kind of a world or a prototype world or a plausible one an example of plausible one and we want to ask Julie to maybe give people a run through of what EAT is. Many of us know but a lot of people here might not and so Julie has prepared a presentation and she is happy to jump into it really whenever so.

Julie: Do I adjust the slides?

Scott: Oh absolutely yeah so. One thing that I maybe you don’t mind one thing that I want to say is that we actually the slides did not upload properly so I’m going to have to upload them again I just realized. but don’t let that alarm you we are going to upload a PDF to the website and I will post the link as soon as its up that Julie can go ahead and get started talking anytime and you can jump in whenever you get them.

Julie: So do people here see them?

Scott: People here can see them and people online can be able to see them in a moment if so.

Julie: Okay so I can so you want to start with the first one?

Scott: Yeah.

Julie: I think one of the most persistent ideas in 20th century art is that of incorporating new technology into art. You of course had the futuristic blind devotion to technology Russian constructivists who attempted to merge art and life the very strict attempt design approaches of the bell house and they were continued by Kepish at MIT with Molinage, Garb [0:04:33] [phonetic] etc and then of course Marcel Du Chance attempt to make art from every day objects. But in the ‘60s there was an upsurge in the interest in technology among the society and among the artists but they were shut out. It seems like such a strange idea now but they were really shut out from technology, computers were mainframes you had to take your little cards that you’ve coded and take them and then wait two days for anything to come back. and the idea of using materials that were not traditional artist materials had just not it was impossible for the artists to get some plastic they could get one sample or a car load of plastic but to get enough to work with was impossible.

[0:05:19]