Autonomous information production

Week 47: Urban Tactics / Atelier Autogéré d'Architecture

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is another event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

This week we’ll be talking with Doina Petrescu and Constantin Petcou, initiators of the Paris-based network Atelier Autogéré d’Architecture (AAA), a collectively-run, self-managed architecture studio which, for reasons we will no doubt want to discuss, translates into English as Urban Tactics.

http://www.urbantactics.org/

http://www.urbantactics.org/documents/AAAposter.pdf

AAA is a collective platform which conducts explorations, actions and research concerning urban mutations and cultural, social and political emerging practices in the contemporary city — with branches and projects in Belfast, Berlin, Dakar, Sheffield and elsewhere. AAA acts through ‘urban tactics’, encouraging inhabitants to take part in the self-management of disused urban spaces, bypassing contradictions and stereotypes by proposing nomad and reversible projects, initiating interstitial practices which explore the potential of contemporary city (in terms of population, mobility, temporality).

It is at the level of the micro-political that they seek “to make the city more ecological and more democratic, to make the space of proximity less dependent on top-down processes and more accessible to its users.” They have initiated and participate in the collective management of a number of ongoing neighborhood projects, involving collective gardens, food distribution, and film screenings.

So-called “self-managed architecture” is an architecture of relationships, processes and agencies of persons, desires, skills and know-hows. Such an architecture does not correspond to a liberal practice but asks for new forms of association and collaboration, based on exchange and reciprocity and involving all those interested (individuals, organisations, institutions), on whatever scale. As they put it, their architecture “is at the same time political and poetic as it aims above all to ‘create relationships between worlds’.” More plausible ones perhaps…

At any rate, those objectives and vocabulary are obviously right up Plausible Artworlds’ alley, as it were. It seems that in the practice of AAA, architecture becomes an overarching metaphor for rethinking, repurposing, reskilling relationships and forms of engagement amongst city dwellers as much as for producing (re)built environments.

Transcription

Week 47: Urban Tactics / Atelier Autogéré d'Architecture

Scott: Hello everyone.

Stephen: Hey Scott.

Scott: Hey there. I think we're still waiting for a few people but they might have stepped away from their computer or can't pick up so we'll just go ahead and let it ring. I guess welcome guys. It's great having you here this week. Welcome to yet another week in this year of Tuesday night events focusing on different examples of what we're calling Plausible Artworlds. I sort of feel obligated to say that at the beginning. Does everyone have good audio? Can you guys hear us there in Paris?

Female: We can hear you well.

Scott: Fantastic.

Stephen: We can hear you well here in Buenos Aires perfect.

Doina: Yes in Paris too.

Scott: Great. Does anyone hear a ringing in the background or are we ready to go ahead and get kind of…

Doina: Yes.

Scott: Okay great. I'll go ahead and stop that other ringing. So fantastic it's great to have you guys here. I'm hesitant to even try to pronounce the rest of your title. Urban Tactics is as far as I get. And yeah I can go ahead and paste. There we go. I don't know Stephen if you'd like to introduce Urban Tactics Constantin and, is it Doina?

Doina: Doina.

Stephen: Doina and Constantin. Hi Doina and Constantin.

Constantin: Constantin please it's not Constantin.

Stephen: Okay. We won't get into – Constantin and Doina are actually Romanian, I think I'm not making a mistake about that, based in Paris and have been working as and are architects actually have architectural studio in the 18th Aranamous so are very decidedly working class part of the city. And have over the past, I don't know, 15 or so years have developed basically a non construction focused architecture studio which they call the Studio for Self-Managed Architecture. Originally in a squatted building formally occupied by the French National Railways. I found a very interesting project called Echo Box in which they involved people in the community in all sorts of activities but primarily in sort of re-dynamiting the green space and the urban space of that neighborhood through Echo Boxes. In other words, building garden spaces on pallets and on skids in a very large space.

That project was very dynamic and is extremely well known, probably the project for which they're best known. And then it had to transform because they left that space and they went into a second space a public forum a public school that left that space. Now they have a new space basically in the same neighborhood. But what they've done and I think what they're going to tell us about is have really diversified and really have expanded out into a kind of a network of similar minded urban tacticians across Europe and beyond. And so [phone ringing]…

Scott: Sorry everyone I thought my bell was meant to be called if not I just turn off. If you want to be added to the chat list let me know.

Stephen: Oh sorry. Okay thank you. Okay so I'll just leave it at that. Thank you for staying up so late and maybe if you could give like a quick half hour, if you can call half an hour quick. Sort of an overview of what you do and why you do it, when you started, why you started, and what you hope to do in the future and then we'll sort of all jump in and ask questions about all that sort of stuff. Constantin.

Constantin: Yes [inaudible 05:24] of course, how do you say? We started building in 2001 maybe one of the, there are many reasons of course, but one is to leaving this area in the [inaudible 05:35] to –

Doina: Can you hear?

Constantin: Can you hear?

Scott: Yes. We'll be adding people to the conference periodically and if they don't pick up for a little while I'll go ahead and stop it. Please continue.

Constantin: So they are many reasons. One it was to act like residents so it was something like local activities probably reason. And another one was to act like occupants in the place where you live because the architect today it's more and more connection with the power and it's dependent on the power and it's subordinate. And of course this kind of production of space for us it was problematic. And we tried in this way by combining our position like a professional, like an occupant when at the same time like original to start a collective process of production of space by bottom up process.

And so it does a very long process it does very typical in the beginning because, specifically in the French culture scene is really unusual. In this moment in 2001 in Paris and because he came to France the only comparison with our practice and our project it was squat movement and it was an interesting movement but went into a very specific population. Young people [inaudible 07:20] something like that and not to be so close. And our project it was mirage oriented to the people with families with background from north of the center Africa or other parts of the world.

Doina: Well but also I would say to whoever, to the ordinary habitant because we didn't choose a specific set of users off of this project and call organizer. We just opened the spaces and let them accessible to whoever wanted to join in. And I think that this is maybe the most radical part of it because to kind of be faced with all this diversity and contingency of the, let's ordinary user, is so what is the most challenging. And it was difficult somehow to keep it long term as we have tried and to face all the conflicts that arose.

But so what we wanted is to forgive the possibility to these people they have chosen to go to have a lot of kind of user specific but also little by little to become more politically aware about what's going on in the city. So when we had the first space it was an amazing space. And Stephen might remember it was quite a unique in Paris setting maybe that the last big wine house that was still empty in Paris three [inaudible 09:44] mentors in which lots of subcommittees starting with garden but then cultural, the political debates was taking place. But when the moment came to leave a certain intervention we had to negotiate and this was a very important moment because lots of the people using this space had never had any, let's say exposure to politics or to everyday life, only politics and they were so much quite effect keeping this project going on. They were prepared to go and fight for it. And for us this was a very important moment to kind of politicize this users that were not chosen, were not political beforehand and they were politicized in the [inaudible 10:58 child talking].

Constantin: I'm not sure if it's clear. Hello.

Scott: Yes you're coming through clear.

Stephen: It's definitely clear I'm trying to kind of give a running commentary of the selling points it was very clear. Hopefully things continue about maybe giving more specific examples too about what the…

Constantin: Yeah. What concrete example, by example because the area was a very poor and prime area so in 2001, '02 and '03 when we started the project there was any [inaudible 11:46] project and all this 30,000 people who live in this entire area they don't have any cinema, any bookshops, any museum, nothing and they were completely related between the railway lanes. And so it was like Iceland and our idea it was to obtain and to use as an empty space because there was a lot of empty space or industrial empty space on the railway without use spaces. Yeah it does do in a temporary way this phase and in a mobile tactic too, because all the empty space there was available for a short year short precise period something between two or four years.

The idea it was to develop a project in an existing priority of our ability of the space but with the capacity to move the project or the device developed to have it on was mobile. The project when this capacity to be no [inaudible 13:15]. So this mobility took priority finally was a very important key to keeping the project ton this reversible suppression.

Doina: It was somehow our main tactic because we were prepared to move and to occupy a lot of space all over the devices that we have conceived starting with…

Constantin: I believe in the garden.

Doina: …the garden made out of pallets. Then we had this series of mobile modules that were adding activities to the garden like we had the kitchen, we had a library, we had a media lab, all this were mobile in fact it were easy to push into another location and they became our war machines and weapons because of this condition, mobility condition and we didn't have any placed on the garden again or the location and now it has been moved for the second time and reinstall again with the same principles yes. So it was a way of resisting and instead of disappearing when the space was closed we multiplied all of the places.

Constantin: Yeah.

Doina: Because he's had the first big space he negotiated three small spaces that would make the same surface so to say. And so now there are several projects in the area that are collected to…

Constantin: The same approach.

Doina: Yeah.

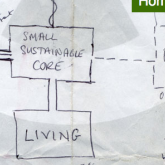

Constantin: In fact what to call the automatic approach or automatic project in the sense to be able to top sell and step-by-step and a long time our involvement and our acknowledge of how to run a project like this to other people. So there are some of them to come just for garden and also to pass to be interesting to cook together or to practice different debate and smaller the [inaudible 15:44] of recycling or something like that. And step-by-step we have a lot of some of them and not a lot of them was able to run many actions, and finally a small group they were able to run all of the dimension of the project, and what to call the assessment manager of the project.

So the project is managed by us in the beginning in the first stage and that's what is culminated by us and the users. And we start doing the project because I [inaudible 16:19] space are these people who know different aspects of the project they are able to run them by this. It's like a leaf who is able to construct all the plant because the leaf has information and other part of the plant they don't have, but the leaf has information about the other plant and is able to put the leaf in the water. So these key people who were involved in many options they are often around the project so they're around the project and some of them they develop new projects. This is what you call a resonated project and automatic [inaudible 17:06]. It's important because for us it's a freedom to knew that project. And so one it was freedom to be [inaudible 17:19 child speaking] to build tunnels and to have the project however they want.

Doina: There is maybe a kind of important aspect to it which is exactly what we call a [inaudible 17:39] process because people would come in the first moment with very limited expectations like coming there for gardening. But because of the whole dynamic, the complex dynamic that was little-by-little infused in the project they started to do other things and they completely changed their attitude. They became more proactive and they started giving them that there were very interesting flea markets run by [inaudible 18:24] forms of artility where economy which were completely their idea, their initiative their adding's to the project. Some of them had stopped to ask a question about the status of the empty spaces and the issues on politics of everyday life and some of them because they became aware were able to continue the project further and to take over the management.

Constantin: Why didn't he ask you to sell an experiment?

Female: Because they didn't actually say cover the rental place but they said ground was on the ground.

Stephen: Maybe you want to actually ask that question kind of like unpack it a little bit. Could you do that?

Greg: Hi sorry. No I was just, this is Greg, I was just curious if you and encountered challenges along the way or things that didn't work quite as well negative as a result to determine what struggles you came up against and how you sort of dealt with that. When I enter urban tactics I think of tactical art of the week. And so you have to be creative in the way you implement them but that doesn't mean that they always work. So I was just curious about the challenges.

Doina: Yeah. Well I think one of the challenge was to come, let's say together at a kind of level of a shared project, because most of the people that came onto the project didn't have any experience of quality practice but they all came with references of, let's say, allotments or facts in guidance in which you are just hitting a plot and you manage it as you watch. And there were lots of conflicts of say individual desires and we have to accommodate so this was one of the challenges. And we tried to put together a mechanism in place to do this like regular meetings in which we discuss all the interested items browsing. But where there was a huge issue around the present of children with items in the garden that not everybody agreed on this because they felt responsible for children that were these African children that were hanging around.

And I think culturally they won't ever come with their parents that were also working during the day. So they came with their older sister that were the ones that sort of would take care of them. And so this is what we recognize also, we recognize the responsibility of their older sister and brothers and we took them seriously. We also kind of asked the children themselves to act as citizens to take responsibilities and in this way I respected them and it was fine. I mean even if they were not condone this type of discipline in children that we are used to. They were completely wild but these brought something important to the project which was a quite challenging energy.

Constantin: I mean this the message is really important to the project [inaudible 23:04] of this account of the people in Whelan because usually it tends to challenge that movement but particularly the people there they have this same values and they have the same reference to in [inaudible 23:20] project. But in other ones after other ones in certain of a tried to up on the project to people who've got really different backgrounds and you imagine there [inaudible 23:38] because our search don't even know from the beginning what kind of rules to, what kind of user guide of the space left to be in shape and left to be proponent. The idea tends to start with the project to [inaudible 24:02] and to discover step-by-step together with other people involved step-by-step to discover the rules in a minimum way so to have a minimum necessary route. And plus trying to discover the best way in our crazy task to establish rules like in homes, like in family so they want us to keep this place clean like in the same stage like he comes to this place so he must close the gate and when he leaves this place because it doesn't mean the gate on the entrance of parents and this space and things like that. So people with different backgrounds and they were able to resume together the space with a minimum conflicts. And this opportunity is not a typical situation but a consumer one.

Doina: Well another of the country where city hall that was a conflict we managed right after we went because we were able at the end to get other spaces that we never at least by this local government the super bowl of the 80s we could would have never managed to get our practice recognized and so as valid as interesting for them. And yeah so we are still somehow in conflict with them and we have an unresolved relationship. But we managed to get them recognized in other places and to provide a favor much more constructive relationship so no other local governments even the second project plays this around this much with some blaze. We had a much better relation with [inaudible 26:44].

Constantin: Yeah but before that maybe it's important to remember there was a sea of conflict some critical moments and when the [inaudible 26:59] because of space because the owner because a railroad company and he doesn't find the advise as building for a big Persian project. And there was a little [inaudible 27:15] of these people who was the key of this space when they buy around the space with 80 other families from the area. So 80 families I made 300 people because they are a big family in this area, maybe more I think. And so they had the key and they don't want to leave this space and so they tried to I evict us by saying yes it's a [inaudible 27:50] project is temporary and you force it to be very strong and to explain a lot of things on a temporary basis.

And some people from some very normal because I review it as very nice thing by literally saying "Yes but I don't want to return home every evening to watch TV." I hear you're able to decide together by also who to invite to what kind of [child speaking] or screening of one they say yeah this program saved my life because of what they mentioned was very important. It was this big space a lot of people they are so ready to find this objectivity. To find connective way and different position, social position to build a gardener, the [inaudible 28:54] it's a matter of decide to [inaudible 28:57]. Usually there was who should honor the position by this society so when we tell them they are unemployed or retiring before the middle age are very long time students because they may not have jobs who made of and this [inaudible 29:18] was able to find a subjectivity. And this is too very important and they start to fight with us in order to keep the project and save the project by this relocation. And this is a real quality for the mention of the project.

Doina: We're just looking at this Web site and the charter position of architecture. And I think we are definitely well for such charter then maybe there is a difference. Because I think we had an experience we kind of – we happen to reconnect charter as an [inaudible 30:15]. But we were fashioned in the experimenting with what arise in order to understand better the process. And at the end we haven't a written a charter and we regret a little bit because it would have been a way of not leaving jus the project and kind of the knowledge that has been internalized but also leaving a trace that can become a record for other generations of the project so.

Constantin: Yeah that could be done with them.

Doina: Hello.

Constantin: You are sleeping.

Scott: Yes. No, no definitely here and listening often writing. Often we'll pause or mute our audio so that if I'm typing it won't overtake the conversation or if someone's typing.

Doina: A couple of instructions I'm just a little…

Constantin: Yeah we can do that. So I tried to show some image and I was better to understand you but what you speak just [inaudible 31:39].

Scott: And just to clarify I think I mentioned or asked some of those questions in succession because I think once Greg had asked about the resistance or pushback that you received I was wondering if specifically one of your goals was to challenge an existing order with your experiments in adult environment. Not too assume that there is a right way to do it or anything like this or where even if that was one of your goals, but I was just curious if it was because in looking over your Web site it seems like on one hand there does seem to be a desire to post challenges they're not necessarily in such a direct outright challenge where that's sort of worn on your sleeve. But at the same time I just want to describe it because I'd like if we can talk about that side of this. And I sent the link to the Camp for Oppositional Architecture and Charter because I was curious sort of where you got stuck on some of those questions.

I mean A for example comes right out and say that they believe in outright dismantle of capitalism or at least fighting against the powers that be through their work as architects. And I was curious if those were some of your goals or if you see what I mean if you had specific goals that you were putting forth.

Doina: Yeah.

Scott: So I guess my question was – well I don't know if that helped to clarify why I was asking that but I guess I can just contextualize it just a little bit in that I think you know through talking with Stephen that we've been talking here for quite awhile about different kinds of artworlds and we're looking at that and we're interested in that, even if they're not self-identified as artworlds. We were really interested in the places where we're afraid of practice getting nurtured and happen and the kinds of structures that people build to create different kinds of procedures for creative life. And our thinking is that artworlds are the place where this happens that allows different kinds of work in the world to happen and it allows different kinds of work she understood as work on some level generally speaking or whatever.

And it seems like we've looked at different, when I say different trends we've looked at artworlds that are built on ideas of open source culture, you know artworlds that are sort of formed around alternative economies artworlds that seek to transform existing institutions where the other hand one seek to succeed entirely [child talking] are so directly oppositional that they can't really integrate with existing systems. And one of the things that we've looked at, I'm only mentioning this is because one of the other existing kinds of artworlds we've been looking at worth talking about are ones that rethink, re-imagine or experiment with the built environment. Maybe even the natural environment too. And you guys definitely do that both of those things. And so I guess I was curious about if you proposed an ultimate goal, not to sort of render you guys black and white or anything like this but if part of your goal of this is that what you help them build, both built and natural, can sustain the kinds of practices, it sounds like you're saying they can. And I guess I just wanted to bring those questions to floor.

Doina: Well I think there is already a quite throw take in habiting existing spaces rather than bending spaces and then transforming them to innovation but also recycle the additions and occupying them in residency the way living them as they were after awhile. So this is a very strong think I would say in terms of occupant towards a big space. But what is not visible and we've managed now to open a window and show some energy is that the social architecture of this project is very important and somehow this is structure to the kind of occupation that we are making as architects. Because behind the – well we propose architectural projects that are processes but that also social processes and a way of representing our project, for example, is through drawing and showing this social network that were formed that were stages within the process that are I think the social structure and the social production of this phase is as important or is even more important than the [inaudible 38:13] production.

So I think this is the particular very important I mentioned of a follower position another [inaudible 38:33] a kind of more than [inaudible 38:37] to contradiction of for the users. Because what happens is what we have done is that we have endorsed some that have matched as the user of the project at the conception and the construction of the project. So it was not asked during the project but to the use of the project the project has changed, has evolved and it still evolves.

Constantin: Someone can help me to explain how to open share a window to show some image.

Scott: Hold on a second.

Constantin: It don't want me to…

Stephen: There's two ways Constantin. One is you can actually a link to where the image is if it's on the internet already or secondly if it's a low resolution file you can simply send it to the people on the chat. You go to in that case you go to Window File Transfers and you transfer the file.

Constantin: Yeah. So it's not say the next part on…

Stephen: You have to grab it. You have to do a screen saver of it and then send it to us.

Constantin: Okay.

Stephen: Constantin if you use grab or if you use a screen save it will be a very low resolution file so it would be not a problem to do that.

Constantin: Yeah.

Doina: Maybe a link we can give – we have the Web site.

Stephen: Yeah a link is good. Ben had a question.

Constantin: I will find the solution and have…

Stephen: Okay.

Constantin: Another way of doing link but just wait you can [inaudible 41:06].

Doina: Yeah I'm trying to read a little bit some of the questions that have arrived.

Stephen: Maybe Ben could actually ask his question because I see that it's a little bit intricate, I think it's quite clear. But Ben are you free to ask that question?

Ben: Yes. Hi there everybody. Yeah I was interested in the references to kind of the use of terminology from Qatari and based on that I was just interested on how you want to talk about the relationship between Quatari concepts and the practices that you're involved in, which sounds really fantastic of course.

But it does seem to me that there is a history of dissent and circulation of these central ideas which is much, much longer than the terminology that you're using. And so really one question is how do you feel that, for example the [inaudible 42:13] enable you to practice in kind of a new way or whether you think you find the terminology useful to describe the practices that you are involved in?

Doina: Well I think that we are using much more Qatari and it's not only by living it but by let's say having contact, direct contact, with the people that practiced it, with people that are not bored. Once the members is getting influence or collaboration or close collaborate and so…

Constantin: I think that's looks good.

Doina: Yea so we are kind of in direct contact with the memory of practice. But I think, and because it's also there are many forums to mean these people to this class and all staff and we situated ourselves quite cautiously in this lineage. So we have tried cautiously to experiment with a transversal for community to create new forms of [inaudible 44:00] in solution because we would love [inaudible 44:04] institution but we try to form, well let's say an alternative where form for validation that has a rule in the background that are managing rather than they are informed. And I think that the rise is – we haven't won bigly with it as a direct cause of it. I think that we use it more as a metaphor or as an autonomy that I think that there are – well constants that were operational in one case and it was like at the end we understood that we had done what [inaudible 45:07]. We experimented with some of these.

Constantin: Yeah. You don't try to apply concept of [inaudible 45:22] from the little ones from the other ones. E tried to create bridge and formation within the experiment of practice architectural, not just architectural but social and cultural. And so you try in time to understand better what you do and in a way you try to develop identity period and don't develop into this practice. I mean it don't try to ply to from solutions in everyday because nobody don't want to follow us in this way. But we try to really leave and thirst them into new life situation together with other people. We try to open new ways to leave in everyday life.

And later when you have time and try to understand better of course you try to give support, to find support from other positions that are within the [inaudible 46:30] and then so other ones. And it's important for us but it's just a way to try to culminate it with other people who view the same references or to create connection by ideas and wage concept back, how to say, it's the other part of our practice is not the more important one. It's important for each one to do and the people and the real time and space and life and the presentation, the communication and the knowledge come later. And then you discover over time in my opinion it would discover later to be Qatari or Thailand or English but it's not labor it's not a brand it's just that there's some coincidences and they're not completely. And I believe it would be rude to be doing that. And we discover the importance of the [inaudible 47:33] scale and the [inaudible 47:34] scale that you discover because you have a practice of or you discover the importance of desire like the support of collective project but the work they come a lot of time later. But it's important.

Ben: Okay thanks a lot for the answer.

Constantin: Okay.

Stephen: Hey Constantin where are those pictures?

Constantin: I sent [inaudible 48:12].

Stephen: You know we're like conafiles here.

Constantin: Yeah. By example what is important for me really for what is real and it's to discover the importance of desire and how you say the [inaudible 48:46] it's something very important as far as [inaudible 48:53] to say the power of the capitalist is to be able to prolong desires to people. What kind of desires, desires to even [inaudible 49:06] desire to have a new iPhone and a desire to have a new car, a trip. There are things right now to say a lot of other [inaudible 49:18] that are important and they're not able to provide desires but I didn't say that. And a need to be important with our practice to be able to prolong desire to ordinary people to run the plan of space to run the plan of fraud.

By inapplicable there are much more, how to say, unemployed people and people who need really some occasion to be find the [inaudible 49:55] but in other programs they're more and more ordinary people, people with jobs, people with family, people who thought to be interesting to find this kind or other desire. And to develop together with them other everyday life practice. So they start to come in the beginning for, I don't know, for a half hour by week and step-by-step they come from two hour by week for everyday with other people. So they changing step-by-step they wait until everyday life which is real important. And it's really self-organizing process nobody don't know who's them and they discover their desires their dimension of this.

Ben: Yeah what you say there reminds me of blocks consideration after the II World War why Marxism has failed to appeal to a wider population and why actually national socialism. And he talked about the warm currents and the cold currents of Marxism, which to me sounds a little bit like what you're saying about desire and the ability of certain ideologies to generate widespread desire or not.

Constantin: And I don't understand your remark yeah. Ben I don't understand your remark. Hello Ben.

Ben: I was saying that your comments on desire and how certain ideologies are able to generate desire sounds a lot like discussions on Marxism in the 1970s and a kind of attempt to move away from what was described as the cold stream of Marxism and to try to reaffirm something more like the warm current and find that elsewhere than simply in economic theory.

Doina: Yeah we kind of had a discussion on the degree about these because we were arguing about what cross gender active which that left us only conduct to revolution or to revolution as a bark but to a kind of more slow and embedded in everyday life confirmation of subjectivity. That might be even more substantial inside.

[Child speaking]

Constantin: So Stephen you don't have questions no. Hello Stephen.

Stephen: Yes yeah. No I do have tons of questions. I have a question actually regarding the variable scales of your practice. I'm still kind of really appreciating what you said about the difference between deductive theory and inductive practice. I think that's a really excellent point and it's something that actually hasn't been pointed out in about 45 weeks of discussion over Plausible Artworlds so I'm really glad that that point has been made.

My question is not about that at all actually it's about the double level in which you intervene. It's on the level of it's always extremely neighborhood based and you've emphasized that that you don't choose the people in your neighborhood it's sort of deal. And that they use and misuse and redefine what it means to use urban space. But at the same time you've decided to do that not only in a neighborhood but kind of in a global neighborhood because if we look on your Web site we see there's a sort of a map of the network of Urban Tactics and we see that you are, I mean you have a project, not you perhaps but people working in kinship in Belfast in Bucharest and around Europe and in Africa in Dakar.

Isn't that kind of doing the splits? Isn't that like the gauntly car between a very local neighborhood no matter how estrogenic or however it is and on a scale of [inaudible child speaking] much beyond. I'm kind of interested to see how and why that's important for you to do that.

Doina: Well I think it's normal to be isolated in your neighborhood and the neighborhood scale is clearly a limitation because it's like a family you are very much depending on the fools in the neighborhood. So from one point of view, and I think that while some projects were doing terrific it's the project thousand it's go beyond the local scale it's in danger to close itself and even to minimize itself by being local. So for us the next one for keeping our practice connected to a letter of similar practice or trans practices was vital and was I would say also a political tactic because in this way we empowered our own practice and we formed it better. I think the network or such type of network it's clearly a way of acting maybe not globally we call this Tran local network, a translocal acting, which is an alternative to globalization I think.

Constantin: And then alternatives to the attention constantly became global and not – it's a scale where you keep the anchoring where the local realities that there are other angles or more [inaudible 57:51] what do you say? What other concernment and this bigger…

Stephen: Issues.

Constantin: …issues. Because you are involved in this very lot of project in their everyday life projects. So it would certainly be the everyday and its rant with kids going Paris and sometimes for something else. So you discover to be practical in a way of which we [inaudible 58:23] to the good work. I think we're limited by the project, by the big dimension of the project. And step-by-step you try to hope to be able to open new direction of our project to act in other case, in other space because there are other concerns, other issues political ones and social ones, important ones too and other case. So in order to be able to act this order case we must create mentors or risings. This is a little for right after this very local experiences which try to move the other little ones that include [inaudible 59:17] people and…

Doina: Also there's a problem in power because all other people we are collaborating with are also conducting local and small projects and they are all about kind of urban action urban resistance. And in this way we neutralize the problems and the findings and also we, yeah it's a little consolidating when we kind of follow each other and we get our practice oh so stronger and better recognize because of this organization.

[Man/child speaking]

Stephen: Scott you had a question there. I don't know whether you want me to ask it for you or are you're probably in a position to ask it now.

Scott: Hey guys I think I can ask. If it starts to get tough then maybe you can take over for me. My main question or the last question I was asking before the scale question came up, or maybe not necessarily before maybe simultaneous, was – oh dear I'm trying to find it just so I can reference but I guess, well I guess the main – I know it's on my mind is that like what do you guys, in all the things that you're talking about that are different approaches to what some people call creative life or approaching the world in different ways, you're not insisting that they do so in a certain way or as artists or as architects or anything like that. But yet when you talk about collective projects, different kinds of collective projects, I think you speak more generally about that. You talk about how, what is it, self-organization through different activities in the everyday can help to build collective desire. I know you guys just, Ben just asked you more about that and you talked a bit about that. But what I guess I'm most curious about is what you feel – you identify yourselves as architects on some – well you are literally licensed architects right.

Doina: Yeah.

Scott: And I'm curious about what you feel your competencies as architects, or as Stephen likes to say incompetencies sometimes, can bring to the equation?

Doina: I understand the question.

Scott: Okay.

Doina: I would translate it a little bit in a different way. So what is this specificity let's say of our contribution to the project as architects yes? Would you agree with this?

Scott: Yes.

Doina: Yeah because I think we have some skills and which I think was quite effective for such a project. One was the knowledge of all the kind of knowledge infrastructure to place things for some publicity and then the knowledge of occupying it in a way that allowed at the same time quite a lot of freedom to others to conform the space but also we brought a framework which made the project more sustainable and the whole idea of mobility and the kind of necessity to also the use of pallets that were in fact quite minimum amount that didn't cost anything, but at the same time it kind of produced a lot yet it produced a garden of lots extensile organization that we made by rearranging the pile of pallet that was always there so that the space was in a continual constellation publication.

So I think this was one of the skills that we brought the project. I think it was also an organization skill that as architects we have which is as I say because we are very kin in making roles so far which are not always special we were careful about the social structure in the project and we were also able to visualize it and we need to discuss all this with us. We used also a lot of visual literacy to guidance us at another violation to the project. And other projects became even more complex in terms of the let's say the big aspects of the project that we have done in the physics in the [inaudible 1:05:52] which is called Passage 66 involved some building while many were building were still building that I think would as occupants we were able to give design and to design again in a way that allows transformation, allowed dismantling and…

Constantin: And this is a very important because I translate in way this catching in another way what architecture is and an architect way. In the beginning of our practice a lot of people they ask us but you have a real practice like architect and our answer is yeah this is our practice like architects. And we explain why our practice is architecture and some people agree are on the socialist like [inaudible 1:07:11] or other ones are a conscious of our practice to be more architecture comparing with the normal way to do business. And one of the things is building another and the ordinary people where are they or are they are already in another project and step-by-step they exchange our image about what architecture is and about what the secret is what urban space is.

And I believe it's very important in the beginning you are less considered like architect by the professional one if you are in France and you are the more supported by artistic cultural institutions so we got a lot to learn. And after step-by-step there's a lot of I don't know political decisioner or the young architect early time they are more and more interested in what you do and they try to open new field. So in a way you develop what you call institutional practice in the professional world of architect. And you tried to return to a renew the production of space to political. Architecture is not just a jumbo of architects it's a big architecture is not look at [inaudible 1:08:45]. And in the normal tradition culture of the production of space it was a business of everybody and the political business of business of everybody. So it's a problem of [inaudible 1:09:00]. So you try to open the process, the architectural through other people who they're able to produce space all their life.

So it's not normal to cook for yourself, it's normal to choose and to render your moves, it's normal to produce your space not just a consumed space. So this equilibrium between production and consumption of space it's very important too. And he include dimension of democracy constructed together in quality way. He include dimension of subjectivity as the space of equal they are able to find subjectivities and [inaudible 1:09:40]. So it's more architectural in a way our space.

Doina: Yeah I see also questions from Steve asking what some of the users brought to the project is. And I think they brought content. And we took the use very seriously, in fact the content of our architectural projects in the sense that we have built as the project was used so that a number for moderns appeared in the midway to the project where new users were necessary, where people wanted to have a kitchen and we built a kitchen. A lot of the kids wanted to have a really rain waterfall in the shape of a flower and we helped him to build it.

So I would say we have taken people's desires seriously and associated them to the conception of the space that they were already using. Yeah is there anything else that we have…?

Stephen: I think Scott asked a question which I also would like to kind of elaborate on because I think it kind of links to this idea that users brought content. When people – I think it was an excellent point too – the people would say to you well so what do you actually do as architect because it's not serious? You're talking about architecture but where is your skyscraper? Where is the opera house that you've built?

Constantin: They're in the Dubai.

Stephen: Yeah exactly. Where is your in Abu Dubai? And you're saying like we're talking about people being in control of their living space and it's like we don't own a Five Star restaurant all we're saying is that people should cook their own dinner. But are you saying in that sense that when people exchange ideas in a kind of a meaningful way that what they're engaged in is something like architecture? Is this like a discursive form of architecture talking about the space in which you live in order to transform in a performative way? Is that what you mean by expanded architecture?

Doina: Well I think this too but not only. I think that we went beyond just talking about…

Stephen: No, no I don't mean that. But let's say the minimum thing because of course you went beyond I mean much beyond…

Doina: But the others too they were really involved in doing. I think this was very, very important but they were keeping making things, if it was only enough to move these pallets and to rearrange them in different way in order to get the space for their party or for fear that they were very motivated to have. We had also dormitories that were made out of a time were books were coming and…

Constantin: I want to answer with the kitchen. In this kind of space, in the space where this limited we found that a lot of amazing uses. They cooked together, the organized themselves flea market and organized themselves also to recycling and for a DJ session, etc, a lot of things impossible to be developed in further architectural space. And you know from [inaudible 1:14:28] how to settle his [inaudible 1:14:31] space and his space is produced by the fuses. And in our space when people that are able to produce a lot of [inaudible 1:14:39] so to produce spaces impossible to develop and in others public or private space. So it's not architecture.

Doina: There is another question here about, which is a quite concrete question from our queue, if we have been commissioned to work is this okay or are we initiated it ourselves without an organization? The Echo Books project was self-initiated but we negotiated a temporary use. So we had a kind of free lease for two years from the [inaudible 1:15:34] company. And this was very important because it was not a swatch without authorization and the fact that it was not like this that it was a kind of real application allowed people that were quite skeptical about being part of illegal projects to part of the project.

So we had even people without papers that found secure in our project, people that didn't have absolutely any political training that they were very, very ordinary people that would fear any exposure. Little by little they got interested and started to understand the joy, I would say, of being together and learning together, thinking together and they claimed together with us again on other spaces. But they were other projects in which we have been invited. I won't say commissioned because in fact we're not paid much. We were invited to define projects to mediate between existing initiatives and spaces to open up spaces.

This was the case in the 23rd of this month again with some [inaudible 1:17:22]. And somehow it continues with other in new [inaudible 1:17:29] and we are living off in this year again in the 20th of this month where we kind of generated a much more faster relation with the local government. Well not with everybody but with even the five persons in the local government that kind of understood the interest of such projects.

Constantin: Sorry with the other number I tried to connect you to and to show some image. Do you see the text about [inaudible 1:18:10]?

Stephen: Where's that Constantin sorry?

Constantin: With [inaudible 1:18:18].

Stephen: Okay hang on.

Constantin: Basekamp team analyst I tried to call.

Stephen: Okay. We have to wait for Scott to come back because we don't have access to that one. So he'll get that and he'll see I guess.

Constantin: So it's some future one so with the other one I tried to hold onto the clever of the cloud.

Stephen: Okay got you.

Doina: Clever.

Constantin: Clever Island to show some image.

Stephen: Okay. Maybe you could say something about what you're looking to do now? What's the kind of future for – because I guess one of the critiques that would be, I mean since I know you I wouldn't make this critique but I guess if I didn't know you, you could say one of the critiques of this kind of initiative is that however well meaning it can be easily kind of absorbed by an overarching recapitalization of urban space. Artists have often been manipulated and architects too in rejuvenating public space for investment purposes. And we've seen that happen in Paris and it's kind of an ongoing problem I guess in every space. So how do you answer that? How do you avoid that kind of a problem? I know Greg was asking earlier about the kinds of challenges you've faced but there's a real challenge obviously one in which you have an answer to.

Doina: How do we contribute to [inaudible 1:20:23]?

Stephen: No not how you contribute, how do you avoid contributing to it?

Doina: Yeah, yeah.

Stephen: How do you stand outside of it? How do you respond in an interesting way to that challenge?

Doina: Yeah because I think that the programs the type of activities that we are generating are, and the type of let's say users that are attracting by these activities there are those that are resisting the [inaudible 1:21:00]. And they identify themselves with this talented spaces which are not in our pool necessarily and they are also exposed to political debates that are critical and that are clearly questioning the situations. So it's not that they're not spaces for leisure and just for having fun but they're spaces of knowledge and political production. And I would compare it with - Echo Books for example we were very cautious of instead of, let's say we negotiated to leave a big space which it was clearly it was impossible to stay there, and we negotiated instead three other spaces. And now the new negotiation there are other spaces that were also claimed.

So instead of having one space there are now seven spaces in the area. And I think it was a multiplication rather than a multiplication of occupations of spaces that are kept even if only for awhile out of the real estate market, out of the beautification. And so yeah I think that from this point of view it's like a strategic, we have transformed tactics into strategies strategic occupation of space for other types of companies that are resisting [inaudible 1:23:22].

Constantin: In another way what you try to do, but I completely agree with your observation I believe to be a very useful one. It is a danger to be recreated to be [inaudible 1:23:37] and of constant to general danger with a lot of things. And in our case you try to be very careful in a very naïve way. In a more strategical tactical way you try to infiltrate the system. And in a Quatarian way what you try to do too is you try to provoke business oblige the people that keep it in the system they are broken by their everyday lifestyle. They don't have time, they don't have desire, they have a full agenda, they have things to be done, they have problems, they have kids, etc.

So in the very first moment you try to create condition to create an opportunity for them to be free to what you call it these are some blogs to escape from this system step-by-step and to be a reassemble together with others one in the new ways. So of course it's a risk to be manipulated or to be…

Doina: Appropriated.

Constantin: …appropriated, but if you create what I would call a [inaudible 1:25:11] illusion then I mean all the people there they know what they want to do. And the risk is smaller. So it's like I don't know it's a topical way but it's what you try to do after you try to obtain other spaces and by collaborating with some [inaudible 1:25:37] but they often might want. And with a lot of habitant we tried to develop a [inaudible 1:25:45] but this kind of space in order to be able to leave to have dealings and competitive ones to have economical activities and to leave with outside from the system. So we tried to develop more alternative way to leave I don't know.

Doina: Yeah I will put it in another way and trying to answer also your question about what are the plans now? How we get a lot bit further. And the plans are to go ahead with this idea of a strategy, with this idea of a networking phases rather than us having individual spaces that are managing according to availability of land. But to kind of think about complimentary roles that this spaces can have and to polarize also existing initiatives, not only to generate initiatives from the space out that the space that we are creating out, but to polarize existing organization that have interesting initiatives around the network.

And we want to as Constantin said, to not only, because especially negotiated now there are spaces in which people are coming during sleep time, when they are working and living in the system, let's put it like this, and they are just coming to be buried themselves in their free time with these activities of gardening or screening or chatting. And we were thinking but what about going harder and leaving in a different way, proposing activities in which people can work, leave, and create in a different way, which means that maybe we have to think at dwellings or maybe we have to think at working spaces that can be integrated in a strategy.

And so we are working towards this and also we try to think about this networks more ecologically and try to create locally close they're different cycles between the networks the relations with which bases are not realized by exchanges. Yeah they're not only spaces that are in connection with each other in ideological connection that materialized by circulations of matter, of people, of energy, of jobs, of information. This is why we call [inaudible 1:29:51] which means at the same time were bound a way of retrofitting recycling the re-band but also a kind of connection or a recognition of the urban with the [inaudible 1:30:08].

Constantin: Did you receive the image?

Scott: Yes I was just receiving them before now and I'm about to upload those three.

Constantin: Yeah they are mopping controversy of each page and a localize person. What is important Stephen to, and I try to complete what she's saying, which is this capacity to provoke political raptions after we leave some projects the people they are run and then send the space is on the project but they are able to reclaim right and spaces. And this is very important it's like the right to the city, it's a right to organize the city to decide in the local and a political way what exactly the city could be. We decided together by habitant. And so it's a risk to be manipulated or appropriate this lesson this way. But you have a lot of patience we don't know we are not sure.

Scott: Yeah.

Doina: Yeah maybe we take more questions if they are anymore.

Stephen: Could you describe just really quickly some of the projects which are happening outside of Paris, like I don't know the Belfast Project and the Berlin Project, the Dakar Project, the Bucharest. Not in detail with Paris but just to give us an idea of if how we might collaborate with you if we don't live in Paris and what we might suggest or what you're interested in developing.

Doina: The project in Romania I will start with this one because this one is the first one. In fact it was even before the Echo Box was based in a town in the mountain, which was a town that was really facing the past communist economical and political transformation. And it was a small town of 7000 co-habitants that had just had one factory that was closing. And they were really concerned with the economy; at least we thought that they were concerned. We a good contact there which was a friend of us that had initiated a single [inaudible 1:33:44] what was called the Foundation for Local [inaudible 1:33:47]. And she wanted to have a kind of information unique where people can find out about what jobs are available in this. It's a town that has still a quite strong growing economy and there are kind of seasonal temporary jobs available the whole year, but they are not – people are not informed about what is available.

So this was one and the other was sort of a big awful one just to showcase the different skills that exist in the city and even a different community was also strong gypsy community living on the outskirts of the town. And we imagined this information unit in which all the parts of the unit were representing some knowledge and existing skills present in the city. And there were also products on selling and there were again products that were local products or products that people would make in a little kind of domestic formula that are goat cheese, jams, or stuff like this, which we guided into – it was really to carry after the tourists so acting that they would become aware of what's going on in the city and also that they would contribute a little bit to the economy.

And everything went okay until a moment when we realized that the city called and said it was supposed to be a partner was starting to subtract the product on the [inaudible 1:36:16]. And this was because there was some interest on the site that it was in fact offered in the beginning by the people itself. But within the city there were conflicting interest that were hidden and we were not aware. So at the moment the product was almost finished almost been offered with again a stove made by [inaudible 1:36:59] older the wood work made by people who were unemployed that they were working the factory that got closed. It was also a green wall showing the different local plants of the area.

So all this was the knowledge after we left and we knew that it's not enough to kind of create agency that will generate the energy of spending but what is important is exactly what we both knew exactly what we feel electable just to have this long period in our mutual learning and explanation of what are the benefits of such a project and the kind of thing sharing the [inaudible 1:37:57] and the project with all those inborn indicating, including the city bowl and probably the right word using the city bowl. So this was a big lesson.

In the Dakar this was a project that I have been more involved in confronting because I often was like student Sheffield that worked for a whole year on this project of [inaudible 1:38:33] that women of the organization in the Dakar region were, let's say the growth, were crafted in an international organization called resolve the [inaudible 1:39:01] secret stuff where [inaudible 1:39:06] was a leader. [Inaudible 1:39:13] is a quite fond of [inaudible 1:39:16] she was a spoken professional for the [inaudible 1:39:21]. So she returned to synagogue and what she had done is to kind of revise the women movement and wasn't maybe movement it was too much it was a woman of an organization. But I tend to spend everyday life.

So while it was the project and it initially was to build 300 houses for women that are the kind of holder of that household for different reasons who are either the report or that particular woman, which is quite unusual and much in country yeah. So it was political from the very beginning and also being organized in order to obtain a mortgage from a social back and then with this money to have access to land. And what we have done is they didn't have money to build and we discussed with them we decided that they should go and tend bending and they should learn techniques of bending. So what we have done with a student when I went into that car was to organize a workshop, a [inaudible 1:41:13] workshop in which we have experimented with different buildings which mean that they weren't interested in because we had done a catalog that they had considered online. And they have children which technically they wanted to learn. And well besides this the students had started the different proposals for [inaudible 1:41:37] farm for the whole year and some of them have passed their Masters with this project. So this was Drakar.

Constantin: But maybe too long. What is important all this area project it was to have different kind of experiences and different political economical context.

Week 46: Ontological Walkscapes

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is another event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

This week, with any luck, we’ll be talking with Karen Andreassian, an ambulant artist based in Yerevan, Armenia, and initiator of a number of collective undertakings in and about the post-Soviet landscape, including Voghchaberd and Ontological Walkscapes, which will be included in the “Blind Dates Project”, opening later this week in New York City.

http://voghchaberd.am/

http://www.ontologicalwalkscapes.format.am

As its name suggests, “Blind Dates” is more or a matchmaking than curated project, pairing up artists and non-artists from “what remains” of the peoples, places and cultures that once constituted the diverse geography of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922). Andreassian’s own contribution is a fragment of his ongoing Ontological Walkscapes project — an invisible but undeniable form of dissent-by-walking against the current regime and its oligarchs.

Inspired by the “factography” practices of the Russian avant-garde (LEF 1923) Andreassian examines two apparently unrelated phenomena in contemporary Armenia: the slow disappearance of 1970s Soviet-Armenian architecture and the shrinkage of public spaces due to the construction boom during the last decade; and the peaceful protests which led to the forceful dispersion of the demonstrators during the last post-presidential election at Azatutyoun [Freedom] Square. With both, the artist takes on the role of a “walker” through whom personal stories of ordinary citizens create a map of places (social space) that are neglected, forgotten, or have disappeared.

Ontological Walkscapes is itself an extension of Andreassian’s also ongoing Voghchaberd project, in which he does literally nothing but accompany a small village near Yerevan as its inhabitants — historically escapees of the 1916 Genocide — cope with the slow but irrevocable collapse of their geological landscape, following an earthquake in 1995, which mirrors the parallel collapse of their geopolitical landscape with the demise of the Soviet Union. Andreassian is the focusing device for a project of which the village inhabitants are the self-organized coauthors.

Transcription

Week 46: Ontological Walkscapes

Scott: So Kathy just picked up an email and this is our first time trying it. It's like as soon as you turn on a mic it polarizes everything you say. So yeah, hey Stephen so you want to hear what Karen ultimately said? And we'll just sort of start this off informally because we have three people on the line and everybody hear me already.

Stephen: Scott I think you're going to have to move closer to the mic.

Scott: Oh yeah.

Male: I can't hear anything.

Scott: Hello.

Stephen: Yeah.

Scott: How about this is this better?

Stephen: That's good.

Male: Yeah that's better.

Scott: All right. I'll figure it out I haven't figured out how to use this yet. But yeah anyway.

Stephen: So you were saying something about what you found out from Karen.

Scott: Yeah so basically Karen finally showed up in New York about eight hours late and the two curators there they were like yeah we don't know what's going on but part of his stick is that he does these sorts of disappearing acts. So I guess they were sort of wondering if well by stick I meant he takes these walks right and he can sort of take a variable amount of time taking them I guess. And so they had no idea what was happening. So basically he showed up and so we were able to talk to him and he said well he didn't really want to do Skype from there he didn’t' really feel equipped to do it even though Quinton offered to go up and help facilitate it and everything but felt that Stephen could adequately describe his work.

So anyway can you guys still hear me okay?

Stephen: Yeah

Scott: Awesome.

Male: I can hear.

Scott: Okay. So yeah that's the way we left it. And somehow it sounded by at least filtered through the two curators there that this was sort of part of what he wanted to do. He agreed that it would be a good idea to have you sort of stand in for him Stephen.

Stephen: Okay.

Scott: Interesting. And also we have Sam coming at a little after 7:00 now around 7:15 it sounds like so we'll do a double feature I guess. So anyway I pasted in this description earlier and Greg and Matthew saw that. I could start to read this out if that would be helpful. What do you think? Hey Stephen would you prefer to sort of talk about these projects a little bit or would it be better for me to introduce by reading this out loud?

Stephen: What I wrote you mean o?

Scott: Yeah I mean it's a little bit of an unusual way to start for us but I think its part of what happens when…

Stephen: Yeah.

Scott: I don't know I thought a full moon but I'm not sure what happens.

Stephen: Yeah okay. So if I understand correctly he's not coming is that right?

Scott: That is correct.

Stephen: Okay. So there's no chance that he's going to show up? No.

Scott: Not before we're finished. Actually there is a chance that he'll show up before we're finished but there's no good chance because they didn't show up in New York until like 4:30 and they were supposed to get there in the morning.

Stephen: Okay. How is that possible?

Scott: I actually don't know.

Stephen: Okay. Well I'm a little taken aback by this I must say, but maybe I could say a few things because I have collaborated with Karen on the two projects which she was supposed to talk about. And I have written about those so maybe I am kind of in a position to have some thoughts on them. I mean obviously it's not the same thing as talking to him because I collaborate with him whereas he initiated those projects.

Scott: Right exactly. And I mean he will actually be here. Oddly they'll both arrive probably after we're done…

Stephen: Okay.

Scott: …just because they're staying here. So I think that's…

Stephen: Okay.

Scott: So I think that's the deal. I mean we also will be talking with Sam so at any point we can move on to talking about Red 76 as well. But it still seemed interesting enough. I mean this was written up and it seems like a very interesting project so it'll be awesome to talk about a little bit if you feel up for it.

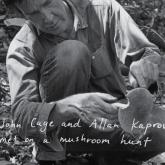

Stephen: Oh for sure. Let me talk about it in this order then. First let me talk about the conditions under which I first met Karen and then I've co-authored two books with Karen. The first one is called "Remaining Time" and the second one is called "Ontological Watch Groups". Actually that title was actually my title originally which we developed together. I'll describe that a little bit how that worked. In 2005 I was invited to be part of a conference in the Ukraine and I gave a talk about what I call Competing Ontological Landscapes, in other words when fictional landscapes are superimposed on physical geographical landscapes, and about the kind of ontological chauvinism that takes place when different predatory ontology's come into contact with other ones.

If doing art criticism and talking about art in a kind of a different way. What's interesting is that immediately after I gave my talk this guy I'd never heard of before was asked to talk. And we all discovered at that moment, he'd been asked by an art journalist, Spanish art journalist which he'd been collaborating to give a talk and what we discovered at that moment was that he didn't speak English at all. In fact he had been communicating with the art journal through his translator which is his wife which he's with in the United States. And in fact he speaks Russian and Armenian but he speaks them with a very severe stutter. And when he's speaking these very sudden cracks emerge in his discourse. The way people stutter and there's that kind of a gap that emptiness between sentences.

And it's very interesting that that's the case because what he was talking about was a very particular dual political situation in the former Soviet Union. So you have to remember that Karen was born and grew up in the Soviet Union and was in his late 40s when the Soviet Union collapsed politically. In the early 1990s the very day that the Soviet Union collapsed this just as a political project there was a terrible earthquake in the southern part of the Union in Armenian near Yerevan and they're the capital. And this town that was about 15 kilometers outside of the capital which was highly appreciated by the members of the Nomenkaltura at the time where they built their datches because that had good hair and good water and so on. The terrible earthquake hit that town and it literally collapsed asunder. All the datches collapsed. The entire town sort of collapsed. There were huge fishers emerged in the roads absolute devastation. And what's interesting is that it happened the very day that the Soviet Union collapsed politically. So you had almost a geological representation of the geopolitical collapse of well I guess the largest country in the world at that time.

And what happened was the big wigs like the Soviet big wigs they cut their losses. They just left their datches in ruins and moved on to the new neoliberal system that replaced communism and went onto sort of privatize all the datches plus the naturalized businesses. The people who lived in the town, I mean the farmers and the peasants, were told by the experts that in fact they had to evacuate the village because things were never going to get better. Now what the earthquake had done was it destroyed the bedrock of that mountainside and it was really just nothing but dirt now and it was inevitably going to collapse more and more, and they couldn't live there anymore. The government offered them a reconvinced of I think about $200 or $250 dollars to go and live someplace else. Now the interesting thing about those people is that they had not been living in that village, their families hadn't been there for hundreds of generation right, they'd actually moved there within living memory because they were refugees from what is called Westerner Media, which is the eastern part of what's now Turkey refugee of the Genocide of 1915, 1916. I mean to escape that they're ancestors had and they moved to this village and became farmers.

So these people were in no way inclined to like move out and move on. So they hung in there and they held their ground literally, they held their ground even as that ground continued to collapse beneath them. And every morning when they wake up they go outside and they see a new fisher has sort of cut the roadway in half, it's really quite an amazing thing and that hear that sound of the collapse. But there's a kind of an upside to it, if I could call it an upside, it is that what happened is the soil itself has been transformed and pushed upwards and it's become an incredibly fertile area for organic farming production, which of course is increasingly on demand in Armenian as everywhere else. And so these people, despite the fact that they're homes are being like permanently wrecked even as they rebuild them, are actually doing fairly well in terms of their vegetables and fruit production. It's a very, very interesting case of what's happening in the post Soviet landscape, which is precisely what is of interest Karen Andreasyan and which was of interest to me as well because I was talking about these ontological landscapes and I mean I wasn't talking about physical landscapes I was really talking about what happens when fiction comes into contact with reality.

And so we went to collaborate on that. And what Karen does as an artist is really nothing whatsoever. Actually I remember in a previous talk here I described what he does at sweet fuckle.

Scott: I remember that. So Stephen but he does do – I'll pull that link up actually and send that to everybody, but I mean he does do something right.

Stephen: He does.

Scott: Right.

Stephen: What he does is he accompanies that village in its collapse and he accompanies the people who live there in their journey accompanying that collapse. He doesn't actually intervene, he doesn't actually build roads or he doesn't do paintings of collapse, or occasionally he does document what's going on and he takes photographs and he's done some video, but those are really just sort of bi-products of an observation or accompanying process. What it is, is that he doesn't say that it's his artwork he just simply says we can look at this incredible metaphoric potential through what these people are doing and my naming it as an artist as a kind of an artistic not as an artwork. But as sort of the art critical lens which we've developed over the history of art we are looking at this it's kind of the essence.

Scott: Yeah hey Stephen I think we had a little lag for a second.

Stephen: Okay.

Scott: And we're back.

Stephen: Yeah. So I don't know exactly where I got cutoff but it's basically his presence as an artist, his role, is just being there and accompanying those people or accompanying that village in its collapse and accompanying those people in their incredible kind of trajectory. And that project was an object of a book which we did together called "Remaining Time" in reference to the [inaudible 16:17]. It entirely just sort of collapses because of the erosion of the underground river beds led to a very different project when it came into collision with an unexpected turn of political events.

[Inaudible audio breaking up]

Stephen: Anyone else.

Scott: Yeah we're here. I don't know if you saw that but the last few sentences, actually the audio interested sounded like you were stuttering. And at first I wasn't sure if you just really were and then it started fragmenting out to the point where we were pretty sure that it wasn't that and then you got cutoff.

Stephen: Okay. No I'm not given to [inaudible breaking up]. In public space, public expression it's just a way of life as people's life has become much more difficult since the end of the Soviet Union. I mean the Soviet Union was obviously a disastrous political culture but it provided a certain potential for, I don't know, development in life that has literally disappeared with neoliberal capitalism. And it's palpable each time I return every year and a half or so to our meeting to see the general decline, the general rising in frustration and general depression.

Two and a half years ago there was a presidential election the election was totally rigged and the man who was proclaimed President at the end of it obviously had engaged in massive electoral fraud and was not, well of course we know these sorts of things is not specific to places like Armenia it happens in very large and old republics all over the place, but it led to very large demonstrations and those demonstrations went on and on and on until the government ordered that they be stopped or that the army to fire live bullets on the demonstrators which they did; they killed at least 10 people. Demonstrations were banned and this is where the project that Karen will be presenting a fragment of in New York began, is that they wanted at once to stop the demonstrations but maintain a return to normalcy. And so they couldn't simply say that people were not allowed to walk in the streets they just were not allowed to demonstrate in the streets.

And so what developed was I think one of the most original and yet invisible forms of political dissent which has emerged over the last little while is that in one of the central parts of Yerevan people just began to walk. In other words, they would meet every night at about 7:00 and they would just walk around and around and around this circle in the park. They wouldn't have banners, it wasn't a demonstration it was simply walking, but it was walking political because the regimen knew fully well what these people were doing but it couldn't exactly demonstrate or prove that that's what they were doing because it didn't look like they were doing anything except walking because they weren't doing anything except walking. But they were walking with a political intent. And I think what struck Karen about that and it's certainly what struck me about it is that that's very close resemble, this kind of invisibility but undeniability is very similar to something which happened to art in the course of Modernity is that things could actually become, while remaining what they are could become propositions of what they are.