Plausible Artworlds - The Book

Introduction

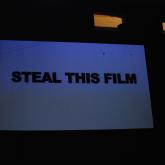

Plausible Artworlds is a project to collect and share knowledge about alternative models of creative practice. From alternative economies and open source culture to secessions and other social experiments, Plausible Artworlds is a platform for research and participation with artworlds that present a distinctly different option from mainstream culture.

The aim of the project is to bring awareness to the potential of these artworlds as viable “cultural ecosystems” that provide both pedagogical and practical solutions to a range of emergent socio-cultural challenges. We view Plausible Artworlds as an opportunity to discuss the interdisciplinary role of artist as creative problem solver and the expanding notion of what an artworld looks and feels like.

Please accept this book, and online expanded version, as both an introduction and invitation to join us in an ongoing collaborative effort to research, discuss, and work towards new Plausible Artworlds...

Attribution

Responsibility

Contact

Download

User Agreement

Allies

FAQ

- How many kinds of artworlds are there?

- Why do you insist on writing “artworlds” in a single word like that? And why do you always use the plural form?

- If what you say is true, then no world is “a world unto itself.” How do artworlds mesh with other lifeworlds?

- Wouldn’t it make more sense to just try and integrate the mainstream artworld rather than trying to change the world? It seems juvenile, utopian even dreamlike to try and change the artworld or any other world!

- But what you insist on dismissively calling the “mainstream artworld” is actually a very plural environment! In the name of art, one can get away with almost anything! Is that benevolence genuine or just an illusion upon which its hegemony is founded?

- What you call “plausible artworlds” is actually a description you ascribe from without. The projects you invite to take part and describe as plausible artworlds were not initially conceived as such. There would seem to be a difficulty inherent in representing an artworld when one is immanent to it.

How many kinds of artworlds are there?

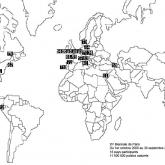

“Kinds” is a nice way of putting it, since it dedramatizes the whole question of taxonomy – which is important to us since Plausible Artworlds focuses on the singularity of its “examples.” The short answer, then, is that there are as many kinds of artworlds as there are examples. However, for convenience’s sake we have drawn up an informal typology of several “kinds” of artworlds we’re interested in examining: Organizational Art; Secessions and other social experiments; art(www)orlds and open-source culture; Alternative Economies; Autonomous information production; Archiving creative culture. The list is anything but exhaustive, and it may even be less helpful than misleading given that the projects we’re looking at tend to overlap several of those “kinds” and remain ultimately undefined by any of them! Still, the list sometimes helps us be sure we are striking a balance in terms of what features of the mainstream variant people are seeking alternatives to. We deliberately avoided categorizing artworlds geographically: the artworlds we have looked at have been from all latitudes and longitudes and we’ve found as much common ground between the most far-flung as diversity amongst groups in close proximity to one another. The important thing, is that the projects actually exist, for again, this is not about “possible worlds” but all about looking at experiments exemplifying “plausible artworlds.”

Why do you insist on writing “artworlds” in a single word like that? And why do you always use the plural form?

For one thing, so that those very questions get raised!

It was Arthur Danto who first gave currency to referring to the artworld as a discrete, relatively autonomous entity requiring a single world: not the sphere of the world where art happens, but a world unto itself, with its own ontological specificity. As he puts it,

an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld.

Something has happened to art that makes it different than any other walk of human activity – precisely because anything can be art without ceasing to be whatever it also happens to be. Danto again:

These days one might not be aware he was on artistic terrain without an artistic theory to tell him so. And part of the reason for this lies in the fact that terrain is constituted artistic in virtue of artistic theories, so that one use of theories, in addition to helping us discriminate art from the rest, consists in making art possible.

Of course, we don’t want to underwrite the sort of separation between the artworld (the mainstream, museum- or market driven variant) and other life worlds the way Danto does! Quite the contrary, which is why we follow sociologist Howard Becker in pluralizing the term. In his book Art Worlds (1982), Becker offers a plausible definition of that concept:

Art worlds consist of all the people whose activities are necessary to the production of the characteristic works which that world, and perhaps others as well, define as art. Members of the art world co-ordinate the activities by which work is produced by referring to a body of conventional understandings embodied in common practice and in frequently used artefacts.

Art, in other words, is not the product of those professionals of expression known as artists alone; it can emerge, be sustained and gain value only within the framework of a specific artworld. Interestingly, Becker always speaks of artworlds plural – as if there were many of them, as if others were possible, as if still more were plausible. What is a plausible, as opposed to a merely possible or just plain existent, artworld? This project stems from the desire to unleash the potentiality of the plausible, as communities and collectivities around the world seek to redefine new, more plausible artworlds. For in a sense, what could be more implausible – that is, all too dismally plausible – than today’s mainstream institutional artworld? The project is thus premised on a desire for irreducibly different plausible artworlds, not merely contrived takeoffs on existent organizational forms; a desire born not of a perceived lack or impoverishment of current models, but stemming like all genuine desire from a sense of excess of collective energies which are proactively coalescing in new artworlds.

From a philosophical perspective, it may seem a moot point to insist on the plurality of worlds. As Nelson Goodman eloquently argues in Ways of Worldmaking – following upon William James’ A Pluralistic Universe –

if there is but one world, it embraces a multiplicity of contrasting aspects; if there are many worlds, the collection of them all is one. The one world may be taken as many, or the many worlds taken as one; whether one or many depends on the way of taking.

Why, then, insist on the multiplicity of worlds? Discursive strategy has something to do with it: it seems far more conceptually satisfying to insist on the multiplicity of artworlds than the overarching, all-encompassing, all-inclusive presence of a single artworld. It also seems important to stress that we are not talking about multiple possible alternatives to a single actual world; but of multiple, actual and hence plausible (albeit embryonic) worlds. But these plausible artworlds are not other-worldly: all worlds are made from bits and pieces (assemblages of symbols, words, forms, structures and still other assemblages) of existent worlds; making is remaking – though the outcomes can be incommensurately different.

If what you say is true, then no world is “a world unto itself.” How do artworlds mesh with other lifeworlds?

An artworld is a relatively autonomous, art-sustaining environment or eco-system. Outside of an artworld, art – as it is currently construed – cannot be sustained over the long term. Art can, and of course does, make forays outside of its established circuits, but it invariably returns with the booty: repatriating into the confines of the artworld the artefacts and documents it has gleaned in its expedition into the lifeworld. This is mainstream art’s predatory logic, all too reminiscent of colonialism; and though it may push back the boundaries of the artworld, it can by no means reconfigure or imagine any plausible alternatives to the status quo.

On the other hand, contrary to what the spatially determined metaphor might misleadingly suggest, an artworld is not a discrete “world” unto itself, un-tethered to the lifeworld. Spatially, these “worlds” are overlapping; there is nowhere that the lifeworld is, that the artworld cannot go.

Their distinction is systemic (or chemical, like oil and water) not geographic. As ought to be obvious to any critically minded, participant-observer, the current mainstream artworld – and the plethora of variants which, in our pluralist societies, thrive upon it and parasite its resources, providing it with a permanent pool of innovation – curtails art’s potential, impedes its unfettered development, defangs it.

Artworldly economies are inevitably bound up with other, broader economies. But plausible artworlds need not be mimetic of the restricted economy of artificial scarcity, which sustains the exchange value of art today; they may be linked to a general, open-ended economy. A plausible artworld is an inherently critical proposition, in that it embodies a questioning of the apparent self-evidences of what an artworld entails: Does an artworld imply a reputational economy? Is an artworld premised on the struggle for recognition? Is an artworld necessarily founded upon the almost self-evident “holy trinity” of objecthood, authorship and spectatorship? That is, on the model that an artist produces objects for consumption by an audience?

Though artworks, artists and audiences have become naturalized features of some artworlds, they may be entirely foreign to other, equally plausible, artworlds. An example from fiction may help bring out the unforeseeable though plausible properties of competing or parallel world orders. In his fictional essay, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” Jorge Luis Borges describes “a certain Chinese Encyclopedia,” the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which it is written that animals are divided into:

1. those that belong to the Emperor, 2. embalmed ones, 3. those that are trained, 4. suckling pigs, 5. mermaids, 6. fabulous ones, 7. stray dogs, 8. those included in the present classification, 9. those that tremble as if they were mad, 10. innumerable ones, 11. those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, 12. others, 13. those that have just broken a flower vase, 14. those that from a long way off look like flies.

As Michel Foucault admits in his preface to The Order of Things,

This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of thought—our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography—breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old definitions between the Same and the Other.

This sort of artworld-shattering laughter may well prove contagious freeing us from clutches of a single world, leading not to a “Noah’s Ark” of worlds but a broader spectrum of plausible, mutually irreducible artworlds.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to just try and integrate the mainstream artworld rather than trying to change the world? It seems juvenile, utopian even dreamlike to try and change the artworld or any other world!

One has to be pretty mean-spirited to find much wrong with dreaming. But what I like best about dreams is that they put the lie to the increasingly prevalent idea that we all live in the same world – the very quintessence of contemporary ideology. Clad in the decidedly dad-reminiscent rhetorical garments of “common sense,” the one-world argument is regularly trotted out by our neoliberal realists to encourage us to fall into line, wake up to reality, singular, and give up our insistence on alternatives to the merely existent. In the name of the efficient governance of the existent order, they trivialise the fictionalising imagination – that is, the imagination that splinters and multiplies the real – as utopian dreaming, claiming that the real is one. But in making such a claim, they let the cat out of the bag – if only because everyone has that extraordinary and yet perfectly ordinary experience of dreaming. Everyone experiences the fission, fusion and overlapping of ontological landscapes that is the stuff of dreams. Dreams – however stereotyped, reassuring or troubling – are the most basic and intimate form of that world-fictionalising function that adds an “s” to the notion of a world. The possible and impossible worlds of dreams, their very plurality, should be enough for us to intuitively refuse the injunction to align our dream worlds with the so- called “real world.” And an injunction it invariably is, because the very mention of the “real world” is intrinsically congenial to the powers-that-be.

A generation ago, Herbert Marcuse sought to defend dreamspace as a placeholder if not indeed a crowbar of the imagination in the established order.

Today it is perhaps less irresponsible to develop a grounded utopia than to write off as utopian the idea of conditions and possibilities which have for a long time been perfectly attainable.

His point, I take it, is not just that other worlds are possible, but that they are this one. However, I am prepared to make a brief concession to the realists in the form of a thought experiment (realists can’t possibly like thought experiments – they fly in the face of their whole mindset, so it isn’t much of a concession anyway). Rather than talking about possible worlds, let us consider plausible ones – and not just of the conjectural variety but worlds which have actually found some inchoate form of embodiment. Which is why we love so much Miss Rockaway Armada’s self-description:

We want to be a living, kicking model of an entirely different world — one that in this case happens to float.

But what you insist on dismissively calling the “mainstream artworld” is actually a very plural environment! In the name of art, one can get away with almost anything! Is that benevolence genuine or just an illusion upon which its hegemony is founded?

It must be clear that those would-be artworlds that are merely parasitical on the mainstream artworld’s resources – its money, its reputational economy, its conventions, its acceptability – are not plausible artworlds, but merely a by-product secreted by any intelligent system (and an artworld is an intelligent system) in its attempt to shore up its legitimacy and ensure its long-term hegemony. One is never more enslaved to a system than when one imagines oneself to be free from it – and given the blasé, been-there-done-that outlook of many critical artworlders, it is staggering to observe their epistemological naiveté in overlooking the extent to which they and their contrivances are the pure product of the mainstream artworld. To imagine a substantively different artworld necessarily entails deconstructing the conceptual norms and conventions (along with the devices through which they are expressed) in order to reconstruct a plausible alternative. Such apparently self-evident conceptual institutions as objecthood, authorship, spectatorship, visibility and a host of others need to be subjected to sustained and systematic scrutiny in order to reveal them as the product of history (an inheritance of the Renaissance) rather than the natural order of all things artistic.

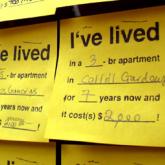

We assume, for instance, that art must engender expectation (see something, do something, be something) and that an artworld can be circumscribed by the horizon of expectation specific to it. But is expectation a necessary or merely an artworldly contingent feature of art? Any plausible artworld must provide for the sustenance of those who are in it. But does that necessarily entail an economy – that is, an internal order of monetary and reputational value where expenditure is ultimately commensurate with income, loss on par with profit?

What you call “plausible artworlds” is actually a description you ascribe from without. The projects you invite to take part and describe as plausible artworlds were not initially conceived as such. There would seem to be a difficulty inherent in representing an artworld when one is immanent to it.

Very true. Because of divergent value systems, it is comparatively easy for one artworld to observe another and objectify its workings. But to understand why there are artworlds, one requires empathetic, and thus to some extent participatory observation, which at the same time makes any fully integrated representation impossible – for how is one to account for one’s internal yet privileged observation point? To put it differently, no transcendent perspective is available on the artworld to which we are immanent. This paradox, which tends to further naturalise the status quo, cannot be wished away. It means that there is no outside perspective from which to observe and deconstruct the artworld.

In an incisive article, entitled “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique” drawing heavily on the work of Pierre Bourdieu, institutional-critique artist Andrea Fraser writes:

Just as art cannot exist outside the field of art, we cannot exist outside the field of art, at least not as artists, critics, curators, etc. And what we do outside the field, to the extent that it remains outside, can have no effect within it. So if there is no outside for us, it is not because the institution is perfectly closed, or exists as an apparatus in a ‘totally administered society,’ or has grown all-encompassing in size and scope. It is because the institution is inside of us, and we can't get outside of ourselves.

Though there is something not only frustrating but logically scandalous about this kind of discursive self-limitation, which only just allows reflecting on one's own enclosure, Fraser’s position deserves to be taken very seriously. In the face of art’s enduring desire to break free from the by now quite implausible mainstream artworld, Fraser maintains that art is, and must by definition be autonomous.

With each attempt to evade the limits of institutional determination, to embrace an outside, we expand our frame and bring more of the world into it. But we never escape it.

This is a schoolbook-class instance of one-world theory at work in the artistic imagination, or what remains of it.

There is not single recipe for thinking out of and around this kind of logical closure, but again, we must be clear not to merely play at finding alternatives – tantamount to mere gaming in a slightly eccentric creative sandbox that the mainstream is only to happy to provide and maintain. Perhaps then our best prospect is to imagine the artworld to which we are immanent, yet with which we are dissatisfied, as if it were freed from the normative structures that curb art’s potential. And rather than seeing that plausible space as empty – without authorship, without spectatorship, without visibility, without objecthood and so on – to see it as replete with plausible potential. A note on the plausible, to suspend reflection for the time being. Unlike the possible, which implies an as yet unactualised variant on a presumed “real” world, the plausible almost inherently invokes worlds in the plural. In Nelson Goodman’s words,

With false hopes of a firm foundation gone, with the world displaced by worlds that are but versions, with substance dissolved into function, and the given acknowledged as taken, we face the questions of how worlds are made, tested, and known.

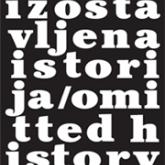

Archiving creative culture

Week 52: Public Collectors & Against Competition

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is the final event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

To wrap up the year, we’ll be talking with Marc Fischer, one of three members of Temporary Services, about his project “Public Collectors” network. In conjunction with this project we will also be discussing Marc’s manifesto entitled “Against Competition” which can be downloaded below.

http://www.publiccollectors.org/

http://publiccollectors.tumblr.com/

http://www.temporaryservices.org/against_competition_mf.pdf

The Public Collectors project seeks to redress what amounts to a massive and systemic cultural oversight whereby countless cultural artifacts are either deemed unworthy for collection by public libraries, museums and other institutions or the archives currently in existence are not readily accessible to the viewing public.

Therefore, Public Collectors invites individuals who have had the occasion to amass, organize, and inventory various cultural artifacts to help reverse this bias by making their collections public. The purpose of the project is to provide access to worlds of collected materials so that knowledge, ideas and expertise can be freely shared and exchanged.

An initiative of this kind gains its meaning and importance against the backdrop of the culture of artificial scarcity upon which mainstream artworld values are founded. The majority of this artworld is structured in this way, and not surprisingly so, as competition between individuals is at the heart of free market capitalism. Grants are competitive. Students compete for funding. Hundreds compete for a single teaching position. Artists compete with artists – stealing ideas instead of sharing them, or using copyright laws to prohibit thoughtful re-use. Artists typically compete for exhibitions in a limited number of spaces rather than seeking alternative exhibition venues. Artists conceal opportunities from their friends as a way of getting an edge up in this speculative capital-driven frenzy. Gallerists compete with other gallerists and curators compete with curators. Artists who sell their work compete for the attention of a limited number of collectors. Collectors compete with other collectors to acquire the work of artists. Essentially, these are the many reasons that make Plausible Artworlds plausible; that make alternate artworlds, premised on pooling resources and mutualizing incompetence, so important. We felt that it was all too fitting to conclude 2010’s discussions with some words that might help describe art beyond competition.

Transcription

Week 52: Public Collectors & Against Competition

Mark: Hello.

Scott: Hello.

Mark: Hey.

Scott: Hey can you hear me okay?

Mark: Yeah.

Scott: Sweet. Okay. Give us just a quick sec to make sure the audio all works and everything or not. How about now? Is this better now?

Mark: It sounds good to me.

Scott: All right cool. So Mark welcome, it's great to have you in on this chat. If anybody gets dropped from the call just let us – please flag somebody down in the text chat and we can add you back or if anything else if you need anything just let us know and we'll try to keep the text chat and the audio synced. Just a tiny announcement. Also if anybody doesn't want to be recorded let us know but I guess staying on the call assumes that you do want to be. Yeah it's awesome to have you Mark finally to talk about Public Collectors Project as part of this series.

Mark: Yeah thank you. I'm getting a little echo there is that okay?

Scott: Yeah let's see. Do you have headphones by chance?

Mark: Not on me at the moment.

Scott: Yeah if you turn down your audio just a little bit it might help cut the echo.

Mark: Oh okay. How's this?

Scott: It sounds good for us. And so this week everyone –

Renee: Oh great Adam's here.

Scott: Mark as long as I understood that properly you'd like to have a really informal chat.

Mark: I mean whatever works. I'm trying to figure out how to turn off the chat notifications that are popping up crazily.

Scott: Oh right on Skype. Yeah I think one thing you can do is if anybody actually really cares about this you could go up to your Skype preferences and then there's a flag called Notifications and you can uncheck your little notification boxes…

Mark: Oh okay.

Scott: …and you won't get all those little notices. It might help. Oh yeah there's a couple of new people in the chat we should probably add.

Renee: Hi Mark.

Mark: Hi Renee, how are you doing?

Renee: Good how are you?

Mark: I'm well.

Renee: Good so am I. Very briefly here before I depart tomorrow back to Amsterdam.

Mark: Oh I'm sorry [inaudible 03:27].

Renee: Yeah. Well you know it's the Philadelphia holiday thing.

Mark: Yeah.

Renee: Are you in Chicago?

Mark: Yeah.

Scott: Yeah Mark why aren't you here dude?

Renee: Yeah why aren't here dude?

Mark: I'm sorry [inaudible 03:49].

Scott: Oh really from this side too.

Renee: Yeah it's hard to understand.

Scott: All right hold on a sec let me mute ours and see if it's us.

Renee: Okay.

Mark: Okay that's the headset.

Scott: All right.

Mark: Hello.

Scott: Yeah hey. So is it us that's doing the buzzing?

Renee: There's a phone…

Mark: Yeah it sounds like it.

Renee: Greg has phone use speakers.

Scott: No phone in pocket. Let's move this back a little bit.

Renee: Is this better? Can you hear us better now? Hello.

Mark: It sounds fine to me.

Renee: Does it sound okay?

Greg: Yeah that sounds better on my end.

Renee: Okay is that Greg. Hi, Greg.

Greg: Yeah hi Renee. How are you?

Renee: Good how are you?

Greg: Good.

Renee: We have a little small party here.

Scott: Totally.

Renee: Party of six.

Scott: And for anyone who hasn't been here…

Renee: Seven.

Scott: …before just feel free to chime in any time. If you want to say something you could just come on up and speak in the microphone or just flag us down if you'd rather do something like that or just hang out. But yeah so okay I think we're all good with the peculiarities of Skype and just the general kind of tech check stuff. So Mark what I think would be really awesome, and I guess just in case there's any question about it, what I was hoping we – and I think what several of us are hoping we could talk about today were two things. One your Public Collectors Project the initiative or whatever you want to call it, the network or whatever, and I think it would be great to talk about that as a proposal for a different kind of artworld or even maybe a component of a different kind of artworld.

And whether it's usually referred to that or not that's what we're looking at, and so just really at any step along the way it would be great to talk about the again competition text which we called a manifesto even though you might not call it that.

Mark: I believe its okay.

Scott: Okay. So yeah I mean if you don't mind would you give like a brief description of Public Collectors for people who aren't familiar with it at all…

Mark: Sure.

Scott: …just so there's some context?

Mark: Sure. I mean I can tell you maybe just an easy way to do this would be the sort of short version would be to read the About Text of the Web site. So just a sort of a basic introduction to the project it has worked a bit. Public Collectors consist of incorporated for collectors around the content of their collection to be published and permit those who are curious to directly experience the objects in person. Participants must be willing to type of an inventory of their collection provide any contact and share their collection with the public. Collections can be based on any GAA web page.

Public Collectors is found under the publication under their many types of cultural artifacts. The public libraries and museums other institutions and archives either do not collect or do make real accessible. Public Collectors ask individuals who have the luxury to a mass an organized inventory of these materials to help reverse this [inaudible 07:56] Collections Public. And that's sort of first happened to kind of basic background. The sort of thing that inspired this for the past 12 years I've been part of the group Temporary Services selling from the group also present tonight in the background somewhere.

And you know and we're sort of basically collaborate work is within the main focus of my creative work for about the past 12 years and in terms of institutional collections this kind of work is usually pretty much on the margins. There's not a lot of collectors support for it. And commercial gallery support or interest in this kind of work when you have a bunch of artists working under a group name. Likewise, one of the groups themselves aren't necessarily very interested in the commercial gallery world either. I am certainly am not that hasn't been an inspiring or motivating kind of place to present the work I do either by myself or in groups.

So a lot of what I do a lot of what I'm involved with you can't just sort of go to a museum and see it, you can't go to a commercial gallery and ask the galleries to pull out material from the backroom or anything like that. So this stuff tends to kind of be hiding either in our own homes or people in our networks. So because a lot of groups are not involved with commercial galleries our group makes a lot of publications and I make a lot of publications. They may also just sort of I'm interested in books I'm interested in cat title things like records. I think the original stuff is important and means something that is different from, it's a digital version of that thing, but I think it's important to have primary experiences with be kind of a sumeria that results from different creative practices.

And so as a result of the kind of work I do my apartment is just kind of filled with years and years of publications made by other people, publications I've been involved if I meet someone new that'd be [inaudible 10:30]. And so if you wanted to see – if you were in Chicago and you wanted to see actually the publications made by the finished collaborative duo I see 98. Well I mean nobody really has this stuff. You can't go to the Public Library you can't go to the Art Institute or Columbia College's Library or Northwestern Library. The best collection of that stuff is probably in my apartment because they're friends and we've exchanged so much material.

Then there are other individual practitioners that I've had a long friendship with who have just sent me many, many years of material either as an exchange or as a gift. So for example, my friend Angelo who Temporary Services worked with on a project called Prisoners Inventions for the moment he's still incarcerated in California and I've been holding onto all of his creative output for about the past 20 years. A French artist Brulo Richard is very obscure in the US just through our friendship I probably accumulated like a six foot stack of material of his work in my apartment. That's not really kind of, it's not being activated at all, it's not really being seen by anyone other than myself, and it's kind of not really doing anyone any good just sort of sitting in boxes.

So the idea with Public Collectors was that people all over the country have all kinds of stuff but it's sort of unavailable, it's not accessible unless they make some kind of disclosure about what they have or once they become more generous in offering that up for viewing, for information. Maybe the way it's accessed isn't that someone comes over to your house but they just email because there's one thing they wanted information about. I try to keep my record collection inventoried which is sometimes a very difficult task. But yeah sometimes someone will email from Holland or from Sweden or something and then they don't need to hear the record they just need like a little piece of information. They need to know do you have a copy of the comic book that came with it is there any chance you can scan that and make a PDF of it? So usually I'll accommodate a request like that and I'll scan this thing and put it up on the Web site.

So there're a bunch of resources I've made available myself and then there's other people who've made artist books available some really, really hard to see things. Steven Perkins lives in Green Bay, Wisconsin and has a tremendous collection of artist books in the sumera and he's inventoried everything and made that available. And Green Bay is an area that doesn't have particularly great museums but if you were interested in certain kinds of art practice I mean Steven has a really extraordinary collection and he's willing to share that. And not only do you get to see the actual stuff but you also get to benefit from his expertise. I mean he's surely knowledgeable about this stuff it's what he's most passionate about. So it's a very different experience to encounter something like that in someone's home with collector present able to illuminate the material, create a context for it, than it is to just sort of find it on a Web site.

Can you guys hear me okay?

Scott: Yes we can totally hear you.

Mark: Oh good.

Scott: We just muted temporarily so you didn't hear the Kung Fu over our heads.

Mark: Okay. So okay maybe you should just leave it there because I'm hearing that echo. Cool.

Scott: Yeah I just pasted in a link for one of the images from one of the collection on the Web site everybody, the Public Collector's Web site. There's just tons of examples of the different kinds of not necessarily art that some of the people are collecting. So what I like about this Mark - I mean I don't know can you hear me okay?

Mark: Yeah. I'm getting that crazy chatter.

Scott: Hold on. Is that better?

Mark: I think so.

Scott: Oh man okay. I don't know what that could be but we moved the mic a little bit away and it's better. So I don't know one of the things that really interest me is that like what Public Collectors is, is more than just a bunch of stuff right. I mean it's not exactly an antique road show like in miniature. Although there's not necessarily a huge difference between some of the items in this something like that. I mean it would be fine…

Mark: Yeah just to be clear that my concern with art with all kinds of the [inaudible 15:45] updates. So it includes – it's moved a bit. What are the problems of the projects is that other people offered to [inaudible 15:58] for direct period that kind of project has really not worked very well. Most people I think sort of like towards the internet they are not actively making the effort to go visit these things. I'm not those requests. And I kind of realized that while I think that part of it is important and I do want to continue hosting these inventories and information to people who do have things they want to share.

The site was getting a lot of traffic and it also made sense that maybe there's some claims that since some people are going to persist in dealing with mostly the Web site that there's more I could offer in digital format. So one way of dealing with that is to start just making PDFs of [inaudible 16:53] obscured books. And obviously there are other sources to this kind of material but compared to say like the underground music world does a really amazing job at archiving I think. There are tons of cassettes that were released in an email in like 250 copies or some like obscure [inaudible 17:16] there are only 500 copies of. Even though these things were available in such quantities someone has done that work to digitize a lot of that material. And of course you always come across things you can't find an MP3 of, but the sort of underground music culture world has done a really good job of spreading things around much, much better than people in the arts or sort of other kinds of Sumera documentation.

So making PDFs of obscure publications was the way of providing something I think sort of needs to be amped up a bit. Like for example, Kim Isaac's "Living the Instructors Book" or the book that White Columns published on the "Artist Run Restaurants". That's a book that's been out of print for a long time it's very, very expensive to purchase in the secondary market. And so I basically just decided just too sort of pop up question about licensing. And I basically just define copyright and scan the material and there's nothing adversity just need assist about. But I focus on things that are out of print and some of these things they've been downloaded several thousand times. I think "Dumb Book" has been downloaded 2000 times so far this year. So these are things that are just very, very hard to see. I've also…

Scott: Sorry Mark I just wanted to mention or just ask you or just clarify that this isn't really only about the archiving of the objects whether digital or physical. I mean it's important to you that people get together in person to look at these things and talk about them right. And more than that when someone agrees to be part of this archive in affect what they're agreeing to isn't just to list their stuff online because like I think Christian's comment just kind of another follow-up question that it begs is do the people that are listing the stuff even have a right to distribute in terms of copyright laws. But more than that I think what they're agreeing to is allow to people to come into their homes right.

Mark: Right or to accompany some of the way they meet at some other location if that's preferable for – I mean another potential I saw with this is that perhaps things could be borrowed for exhibits. And so by making something that's available to someone maybe it's available to show but also there might be a situation where you're chairing something and you really need this one poster or this publication to sort of fill out representation of some kind of practice in a media event.

Or for example, one of the things I collect are records, music or standup comedy they were recording inside prisons. So there's these concert albums the most famous ones for example people like Johnny Cash at the [inaudible 20:44] or Tim [inaudible 20:47]. So there may be pure things like [inaudible 20:50] too or this vocal group where a Motown producer came into the prison but what I was interested in this relationship between people on the inside and people on the outside who are the audience for these records and then sort of movement back and forth between people in prison and the public. And even though much of these records for an exhibit I had maybe 45 examples right, but there are certainly other examples of these records they know about that either can't find but I can afford them.

So if the project existed for this kind of material at the time I was organizing this show captive audience at this gallery 400 in Chicago it would have been really great if I could have approached someone who disclosed [inaudible 21:43] and said hey, [inaudible 21:46 muffled audio] exhibit it's just going to go in front of all and is to be played but it'll [inaudible 21:52] if you try. But it's even knowing that someone had this thing and knowing that there was a way to experience it and to ask about it and find something about it that would have been very useful to me.

So they're – yeah I mean if you do participating in making yourself available to visit it’s not really to duplicate the issue. I mean there are people who participate and you could ask what could record this cassette for or something but that's going to be up to their discretion how they want to be helpful. But basically asking people to about other challenged just inventory collection is incredibly time the way they tested the obligation. So a lot of people saw participation as they began doing that work is really – and so I tended to focus a bit more on the digital industry as I'm looking at [inaudible 23:08].

Renee: We have a couple of questions for you.

Scott: Yeah would you mind coming to the mic.

Lee: Hey Mark its Lee.

Mark: Hey Lee.

Lee: How you doing?

Mark: Good.

Lee: Hey I kind of have a question. I'm pretty familiar with Public Collectors and I just got the Public Collectors blog Ezine from you which I loved. And I was interested in what you were talking about in terms of exhibiting it and how it could – and it's something I'm curious about as a curator I often thing about exhibiting things right and there's always this kind of pressure to show what's new. What's interesting about if you want to curate a show that either consisted of archives from Public Collectors or was something like that obviously there's that pressure of what's new and how do you present something that is a collection I guess? Who is the artist?

Who is the – I know I'm throwing a lot of different junk in here – and I'm kind of wondering about that and I'm also thinking about I obviously love the book that you guys have done that Temporary services did on public phenomenon and I'm also thinking of Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane's book on "Folk Archive". If that's just another kind of thing that you're building toward with your Public Collectors project or if there's other venues more social media ways of kind of getting the work out there to different people. Can you answer any of that or none of that?

Mark: What will help you launch exhibition and using this as a way of pulling things into public view that are usually neglected it's definitely something I'm more interested. And the Art Gallery of Knoxville did in 2008 maybe they did a Public Collectors show which mostly focused on local material. So [inaudible 25:16] has a lot of [inaudible 25:18] who collect these basically the Facebook like old school book with drawings by children then they're sort of in the margins or you have these drawings from late 1800s or early 1900s.

There are archives in digital collections and [inaudible 25:43] for anti sources. This should drag out all of these pages like drawings [inaudible 25:55] or like [inaudible 25:56] houses and the type of photo of a mountain in some ancient text book. And this is the kind of work that there the archive is not and probably would not have sought her out for an exhibit.

Renee: Right.

Mark: But because of Public Collectors participation connected to the [inaudible 26:13] that was really to be able to do that. One anecdote to people maybe being a little reluctant to go to some stranger's house and [inaudible 26:24] just sort of dried things out and bring them to some other sites. So there was an event I coordinated at mess hall where I basically brought all of the [inaudible 26:35] Bruno Richard who sent me over the last nine years or so and laid it on the table and we can go through all the envelopes. We had like this thick packages with hundreds of sheets of paper in them. And still different drawings and sort of copies and layout from books and things like that.

And so I think more and more of that would certainly be a way to do this. Right now I just finished teaching a course called Collections and Archives and this creative practice at Columbia College in Chicago and the student from that class were doing this exhibit. And it's really fun because a student gallery it's normally reduced to showing student photographs, paintings and drawings or videos. And the exhibits kind of crazy if on one hand you have like one student has some slide in event in stage with 35 video tapes packed of like all the watching the appearances and her and her mom and her sister recorded in like the late '90s early 2000s. One student like coupled together her grandmother's salt and pepper shaker collection so there's sort of fancy [inaudible 28:00] equality.

And some other people – another student who's father's death and also didn't have the money so he's mostly distributing a visual thing related to Chicago sports which he feels like every opportunity that he can. And she made a video and start talking in sign language with her subtitles describing all the different ways the [inaudible 28:27] collection which involves [inaudible 28:31] in Chicago to cut down Chicago Bears and Cubs better [inaudible 28:37]. So that's also a way of kind of pushing some of the event spaces to include things that normally get left out because there's some other cultural – you might be quite interesting if you get a chance to properly see it. But there is this sort of outside parameters of what you care about.

And so I mean part of the opera or Public Collectors and [inaudible 29:10] problem can become kind of addicted to somewhere in this culture of all of these people through sharing things and commenting on each other's things. And it's very gratifying to post something and then see [inaudible 29:27] come up with responses or people [inaudible 29:29] and maybe add like a personal note or something. And that's going to be another way of activating just all the stuff that surrounds me in my home. So it's sort of like a project of every day to kind of find some other formulas they had that looked in a lot of and pull out some kind of material like a lot of [inaudible 29:53] flyers for a rally about lack of support for people in Philadelphia but the flyers from like 1987 there's others [inaudible 30:05]. Twenty to 500 people have died so far and that was really kind of in the early days of that disease being identified.

And yeah it'll be nice to have like a more larger focus for [inaudible 30:20] this kind of stuff but there is just one thing that can be added to that larger turnout [inaudible 30:27].

Renee: It's Renee. That was my question just to go back because I've been to your house, I've seen a lot of the archives, and I know what you've been up to for a few years now. And then I was curious about how culminate everything together and then how does the network work so that it's distributed. I remember getting Temporary Services or your mailing a while back, maybe two or three years ago, asking for your public collection. Are you then the hub of everything that people go through you or is it through this personal network or is it that sometimes things come in out of the blue for example?

Mark: There are people that tend to be off the blue of the things that that they want me to host. I mean I have a question about like how much was really all necessary because obviously there's many, many have represented and they're obviously switched the groups...

Renee: Yeah exactly.

Mark: …which looks really I mean much better than I'm doing. And you sometimes hear people asking those groups. Mostly I don't want to put anything between people who participate in Public Collectors. So if someone asks me something I certainly don't want to feel [inaudible 31:49] that person. They may provide their email contact and someone else gets in touch with. So there're been a number who have I've sort of used this on the Web site to promote what they had but then it's on them for smaller and want to do a story about the collector, they want to borrow image for something.

Scott: Hey Mark.

Mark: Yeah.

Scott: Scott here. Just correct me if I'm wrong about but isn't there a difference in the sense between Public Collectors the kind of title project that has to be that in order to show it and Public Collectors the proposal? What I mean is Public Collectors it's not just a specific item right. It's a proposal for another kind of distributed ownership of cultural, not necessarily artifacts or heritage or whatever, but yeah I guess so cultural heritage or cultural artifacts or the things that like give the creative output that we make but also just creative…

Mark: Hey Parker.

Scott: Sorry. You want to say hi to Mark.

Parker: Hi.

Mark: Hi how are you doing?

Scott: But also it's not just showing the detritus of creativity like the creative culture practitioners that make stuff as designers or artists or whatever but also that you teach there's a kind of "creativity" or whatever you want to call it in collecting itself and you're focusing on that thing but not just with like a specific curated selection right. I mean I guess it's a multi part question but he main question is there a difference? Don't you see – let me just rephrase this slightly. Sorry I'm a little distracted. Don't you see that Public Collectors is as much a proposal for another way of doing things as it is a specific set of curated collections that you think are cool?

Mark: Yeah. I mean certainly like it's an encouragement for a cultural of greater generosity which are things that are kind of holding onto. And I think things like with my students certainly like I want to get them thinking about how do you deal with like representing yourself? How do you deal with like representing your own culture or how do you create context or how do you deal with like the stuff that you're interested in that you're not seeing represented in the kind of museums or libraries you have in your cities.

To sort of get kind of strangers possibly working together and they'd be sort of like feeding into a little bit about – but one of the first places that I started thinking about this idea of Public Collectors true it's not anything in the artworld this underground music discussion which we recently just kind of fell apart somehow. Hello?

Scott: Hey we're just adding someone else to the audio.

Mark: Oh okay. And I felt like this sort of online community that mostly kind of existed to discuss underground metal bands and stuff like that but it was really hyperactive. And people really started doing stuff off of the site. They started these people who were kind of talking about their shared interest really started getting someone with medical [inaudible 35:54] on that. But these people really banded together and started making all kinds of things happen in the railroad group, bands helped tours, people raised money for each other or they need medical help. I can't even imagine the number of grown deals that happened as a result of that site. I know that part didn't really have an interest for me.

There were people that I put up in my house because of that place. I could go through places when I travel with these folks in other cities and it was just very energetic as a both discussion forum but also as a thing that became like these real sort of [inaudible 36:51]. But I saw that as a very promising set of development for shared resource and shared knowledge and just kind of generosity that both – I think I'm curious among those many of the people who are participating in this discussion but then I think it much less the balance in the art [inaudible 37:19].

There are people who you're some cultures around collecting or a hobby like thing that's really kind of put the art world to shame and they're there to work together in their noncompetitive and shared information. My wife participates in this [inaudible 37:50] Ravelry which got like a million members and it's much more multigenerational than the forum I was using for music. But it becomes this very all purpose thing. We go down there you talk about all kinds of political issues and certain members within society. People you could probably for help advice or information about home ownership. And it seems to be really credible and very, very vibrant resource. And so I would like to online Public Collector but it has drawn interest from these other kinds of online communities that were strange resource are asked a lot more.

And [inaudible 38:35] has quite a bit of this also but that wasn't setup very well for discussion it's really more of a kind of display tool. And it's very effective for circulating online. The public place that I do for the Public Collector is this concept [inaudible 38:56] but other people do [inaudible 38:59] hundreds and hundreds at a time. And so the curators are used by people not having whatever they needed. I know l scan like this one from something like a fancy like the picture of the month or something. And some of the site is entirely devoted to muffets. Someone had a question about called Rivalry. I believe it is www.ravelry.com.

Renee: Oh knitting and crocheting.

Mark: Yeah.

Renee: Got it.

Mark: I'm sorry I tried to look at the common – like I stopped noticing the chat talk

Renee: Yeah no it's good it's just that I couldn't understand exactly what it was. Cool.

Mark: Yeah.

Renee: Thanks.

Mark: And Patrick's question about tumbler. I mean people usually give right away about to use this sort of very streamlined blog where you can follow the people tweets and then you search together this kind of continuous feed with it. It interesting for work space and it works better for instance something like Facebook but that's [inaudible 40:47]. Yeah I definitely think it was quite [inaudible 40:52].

Scott: Hey Mark, does this seem like a good time to talk a little bit about the Against Competition text?

Mark: Yeah sure.

Scott: We sort of are already.

Mark: I feel like I've been very unfocused and I hope I'm making sense.

Renee: No you're making sense.

Greg: Scott before we go on I have a question about.

Scott: Oh sure.

Adam: Before we get into a wider topic I just wanted to ask this because I follow the blog, I'm a total fan boy of the Public Collector's blog, and my observation it's really cool and just as Uncle Bob's collection of corporate ceramic statues for Christmas towns is not cool. And sometimes the collections that Mark looks at in Public Collectors or that add Public Collectors we're sympathetic to them because they're endearing and sometimes they're alienated and very weird like the Vanilla Ice thing is just sort of an ironic enjoyment. And I wonder if Mark could talk a little bit about how or if he thinks that the blog and what's on Public Collectors really lives up to the populist imagery or the populist project that's described in the About Section.

Mark: Well the blog is definitely sort of more personal extension of – I mean I only post things that I write that are in my apartment. So something like the person on the Public Collectors Web site who collects makeup packaging. I host that on the site because she contacted me out of nowhere and offered that. And I don't really discriminate if someone has something to offer then I will host that. And it's unusual that people do offer I mean there are not many people who have done that. It's a little easier to find people who have something that can be presented in digital form.

But in terms of the material like on the tumbler thing I mean there's a little note in the sort of introduction to that that explains that it's basically a place for small things or fragments of larger things and really kind of an account of the contents of my apartment. It's a way of me sharing without inviting the world into my home to kind of randomly peruse, which really wouldn't be a very effective way of sharing beyond like one or two people at a time. I can open up a box and put something on the scanner that no one else has scanned and put online before. And instantly 700 or 800 people are looking at it and then those people blog it and then hundreds more people are looking at it.

But it is definitely different in that it's sort of my own – it's really more like a personal territorial thing in a way that I didn't really – I don't think – my sort of ideal for their Public Collectors main site. Does that make sense?

Renee: Yeah.

Scott: So I had a question has anyone contacted. Adam, did you say it was Jessica's uncle? Well anyway whoever you were just talking about has…

Adam: Sorry yes, Jessica's uncle.

Scott: Oh okay. Has anyone contacted her uncle about, hey I want to come to visit this collection of stuff.

Adam: No we'd rather not visit but we were treated to a collective. The thing is it's interesting because this is a discussion that goes beyond the thing and the attitude. When I took Mark's spot for selecting we had a discussion about the corporatized takeover of collectives so that people collect things and take back like the impulse versus people coming up with interesting collections of their own.

Scott: Yeah. And are we really talking about not so much like what stuff is collected exactly. I mean of course the stuff is important to the people that are collecting it, the people that are interested, but not everyone is going to be interested in everything in all of these examples. I mean I think that's part of the point rights they're just such a tiny slice of, I don't know subjective population that's going to be interested in like…

Renee: It's a niche in the long term.

Scott: Yeah it's a super niche. And so I guess isn't it more about on the whole - yeah this is really echoing sorry guys.

Renee: Yeah somebody's got their mic on.

Scott: Yeah hold on it might even be us or whatever. Sorry. My question is isn't this project largely about a different form of ownership, because you were just talking about the corporatization of collections or maybe the sort of ethos even for individual collecting that's sort of internalizing that. I mean when you take what you've been looking whether it's a perverse interest if you want to call it that or just like obsessive compulsive or just like a hobby or a life pursuit or vocation or whatever if you decide, hey I'm not actually – I guess my point is the difference between this anti-growth chart is that people aren't looking to sell these collections they're looking to distribute them in a different sort of way. Do you know what I mean? I mean I feel like the network is really important here in this discussion.

Mark: Yeah. And I mean the other thing maybe one of the things that I'm just sort of working on for this exhibit and my students are putting together, I mean I really don't care and in Temporary Services but it's also something like the public phenomenon [inaudible 47:09]. I mean I don't really care about the distinction between the creativity and then some building a collection of like snow globes and thinking about the aesthetics and how it's organized and sort of creativity that goes into making a book about like some other kind of artistic phenomenon.

I mean collectors are like absolutely concerned with so much of the same stuff that artists are concerned with right. I mean they care about aesthetics, they care about content, and they care about history, about the ideas behind things. And when you see this sort of thoughts fully assembled and organized collection of stuff I mean it's as immersive an experience as any of those collection pageant. And I won't say the answer is pushing for these official spaces and institutional spaces to incorporate this kind of stuff. Because I think it holds on better than people like to think some [inaudible 48:21] activity. I mean [inaudible 48:24] these questions and to show them what my students are working on is that each project of theirs is probably at 15 things but that's 15 things time 15 people. And some of the questions maybe like 80 things in them. So visually from this rich experience of stuff there are all these different approaches to organizes, to categorizes it, some of them maybe [inaudible 48:52] source of chronology. And sometimes people are posing more of the personal narratives on the material and context around [inaudible 49:01] or creating pretty different circles for which you would look at it.

But I think after [inaudible 49:10] they're interesting because of course there's this sort of mobile whatever that is kind of like holding my breath about the [inaudible 49:21]. Yeah both of those discussions really talking about where does this history come from, really which history of objects.

Lee: Mark this is Lee again. I think it's really interesting you're discussing like Antiques Road Show. I always kind of found that show when I was a kid I really enjoyed it a lot and as an adult I can barely watch it, in fact I can't really watch it. The one thing I found really interesting about the internet over the past few years is like the ubiquity of video now. It's like I spend so much time on YouTube – maybe I shouldn't – whatever fine I'm proud of it. So I think a lot of people do like there's so much video on the internet people kind of doing everything. There's people dancing on the internet and sharing their dance, there's people doing all kinds of stuff on there and I'm wondering if there's some kind of life to being able to show your work through some kind of video means like walking through the collection if that kind of adds anything or maybe you think it's not really that valuable, I'm not sure.

Mark: Oh no there are lots of videos on YouTube of people showing their collections and talking about them. And I definitely watch those and some of them are really boring, some of them are sometimes the personality of the person or the [inaudible 50:49] it talks about. Some of the are sort of creepy I mean this guy will show you 80 million batman costumes and you [inaudible 51:00] for. They're sort of challenging it's probably more interesting than any of the objects. And then the guy looks like he's not going to be wearing those batman costumes anytime soon. So a really different type of person which is this sort of ideal thing that he's collecting.

Yeah I mean you can do some with that kind of stuff. And thinker and tumbler also I mean come with these really amazing people doing this incredible job of dealing with like their – they have maybe a south card selection like the stuff is just – I wish I could with you to the Chicago Museum of some sort and look at that [inaudible 51:55]. And then quicker those kind of things quite well because you sort of [inaudible 52:09] they're all easy to scan. Yeah the actual object but they do hold up quite well. And then the people are trusting really high resolution to this. So there's some pretty good venues for this kind of stuff online.

Female: I was just thinking it would be possible that these people could have these collections could be improving on them using the internet and such like that. They can check and see what they have, what they don't have so that communicating on it, polishing it up. That's certainly.

Mark: Yeah some of them really nicely network with each other but if you look at this other question about fortune I haven't spent very much time with fortune but certainly like fortune wants to get things done. I mean they're just people obviously are I mean they're incredibly effective at pulling resources and energy and doing some really constructive things right. But certainly in the online community and some of them do get together in the world too. I mean there's [inaudible 53:44] in their bedroom or something.

Lee: Someone asked a little while ago like collecting- I'm sorry I think they mentioned that – I can't scroll up because I don't have access to the computer – but it said something like I think there's a Public Collectors look like what the internet use to look like back in I guess the early 90s or mid-90s, and there's actually I don't remember the Web site and I'll have to look for it later maybe post it somewhere maybe I'll send you the link, but there actually is one group online that does collect old geocities pages and archives them and writes about them and has tons and tons of them saved. And they look beautiful. So I just wanted to mention that.

And the second thing was that got me thinking the artist Cory Archangel actually for awhile, I don't remember when this was this might have been like in the mid-2000s or maybe like the early oughts, but was I think specifically trying to create that kind of style. He still sometimes does but he was making Web sites that look like that as far as I can recall he called that Dirt Style. So it was like he was inspired by the look of those things and was using that as like to create an art style Web site or web media.

Mark: Yeah. [Audio is echoed and muffled] that old material right.

Lee: Yeah.

Mark: I mean I think it's kind of a task but I like to – I mean I guess I sort of admire that in an artist they not only [inaudible 55:54] but still it's a matter of [inaudible 55:57]. People who make time for the preservation or promotion of the artwork is not there it gives some energy to write about it to figuring it out how to get through to some things to sort of lately be [inaudible 56:22] there are a allowed to open a bit for something outside of themselves. Or making contact with their predecessors and actually know the [inaudible 56:35] a fan or something.

Lee: Yeah. One thing that people are kind of discussing I'm looking at some of the text now, a lot of those Web sites they're not really – someone said it's not a coherent structure. And I think one of the things that's interested about those Web sites, what makes it difficult too is basically someone post something and then moves onto the next thing right. And so even though there's like an institutional memory to some degree that's not the exact right word. There's an archival memory in that you can go back and look at the past archives. Basically it becomes the past and we move on it's like your email you archive it when you're in your Gmail and you just kind of move onto the next thing and you kind of forget about it.

So there's something about using those Web sites that doesn't really allow for, I don't know I guess reinterpretation or discussion. I'm kind of waiting for Patrick he said "What I meant was", I'm curious to see what he's about to say.

Mark: Yeah I mean most are interested in [inaudible 57:49] of how you archive the stuff that gets generated by the discussion but there's this [inaudible 58:03] these really great threads of [inaudible 58:08] who try to redraw their favorite album cover on [inaudible 58:11] it's really kind of basic graphic programs idea in a couple of minutes or something. And they were noticeable for doing the [inaudible 58:26] and kind of pulling them together so you can fill like an example of the same [inaudible 58:31] of creating other [inaudible 58:36] three minutes.

And you have to go on different Web sites to find that thread and one form completely different [inaudible 58:48] occupation so there's like a lot of stuff on the internet that's being wiped out really quickly as [inaudible 58:58] and go and things like that. And it's the joy just be [inaudible 59:02] in how you want to preserve. I actually think that preserve is something you care about but you do that when you publish [inaudible 59:17] this kind of amazing of collection of some internet creativity.

Scott: I think what I would ask you Mark if you can think about this because you've definitely been a huge advocate of keeping an archive of making friends. And I've heard you actually criticize because we don't do that. But do you think that there is space now for this kind of culture that we're talking about that has no interest whatsoever in ever creating a past that is constantly evolving, that no interest other than to actually like make a joke and then sending action right at the moment to forget about to completely.

Mark: But what was the question part of that?

Scott: The question part is how you feel about this evolving culture because I think that's how I would describe the four hands and the other subcultures. I don't like to say culturally but whatever you want to call them. But these structures, these groups of small evolving communities of anonymous people who just take action and then disappear and they don't really care about archiving. And you're sort of coming from this culture and you're talking about this sub-culture and this unit culture that does archive and does keep a memory history. So where are we going if that is the future and these are the future? Are you the last best of keeping some cultural archive?

Mark: No I mean there are lots of people who like often try to figure out [inaudible 1:01:00] or going back and it's very hard to [inaudible 1:01:08] ago. A lot of people look at the other stuff like it's this discussion that I [inaudible 1:01:18] for a long time it's [inaudible 1:01:23]. I let you know that it's lost because most of them are not [inaudible 1:01:29]. But of some of those discussions I think are quite useful 20 years from now maybe.

[Too muffled to make out context]

Renee: What did he say?

Mark: [Too muffled to make out context]

Renee: I'm sorry what did he say about the…?

Scott: Mark we missed what you just said can you say it one more time.

Renee: Sorry.

Mark: I think one of the [inaudible 1:05:44].

Greg: Just to [inaudible 1:06:06] can you talk about – one of the things I just remember that was really great recently is when you posted the prison catalog images on Public Collectors and it was actually a political response to the strikes in Georgia. Can you talk about your feeling and maybe some of the other people on Public Collectors of people who are collectors like how politics can function and the collection can function politically to bring – like when you brought all these images out of prisons it was disturbing to see all these really disturbing images of restraints of humans that were not old and medal and something in the 18th Century but very contemporary.

Mark: Yeah. I look the version that if you're thinking about this one kind of material that maybe sort of manicurist and then I sort of put something that has a really different feel to it, a really different texture to it. Right now there are probably close to 800 people who follow the tumbler blog and then they follow it for extremely different reasons. So one person may take a whole bunch of stuff that's like typography or some point of medal or like the science fiction and covers or something. And people start following because they're interested in that. But it's fun to sort of switch gears on them and then give them like nine examples of restraints that are in the market.

[Too muffled to make out context]

Scott: So Kristin just had a question. Mark you are not really promoting that everyone should archive everything right. I mean isn't it the case that people are constantly collecting and that aren't you as critical of the kind of violence inherent collecting. And even just some of the problems of collecting. I mean this project isn't really a promotion of collecting like just in general right. Isn't it a promotion of distributing ownership of collections?

Mark: Well I shared enough resources that because they reside with private individuals are just not those. They would be in vast parts of the country where they'd normally be and sort of terrible public libraries but there's all this stuff that people are holding onto which you somehow see what was there these pictures would be filled with riches and with history and which really needs some material that it's just sort of a presence certainly in business.

But Kristin's question about editorial direction or value there's a difference the kind of focus thinking that goes on and it's like the collection I have are the prisons and the albums recorded in prison. The less material I've given an enormous amount of thought to. It's something that has gone on time with but they're also [inaudible 1:11:05] they just sort of [inaudible 1:11:08] maybe interested to share but I'm not ready to make any given about them or write a book about them.

But nevertheless you get someone and give them to me I have a choice to just to sort of disappear into your box or be shared in some way but not with the [inaudible 1:11:30] behind but maybe someone else can do more with it like with those [inaudible 1:11:38] there's one that I took a cover of which is sort of a really strange interpretation from common form of the abuse at Abu Ghraib and the characters and just completely re-imagine of this [inaudible 1:12:09] woman who had [inaudible 1:12:10]. I mean it's really like quite remarkable. And I felt that it was a bit racist but I didn't feel like I felt the desire to share through guest forum but I did put in the cover of it and there was someone who were renewing their PhD research on relationships between foreign and violence and the war in Iraq who was really interesting.

So he contacted me and begged me to write the [inaudible 1:12:52] and we do more research so that was really helpful to him. So I need to be the expert in that comic book but taking the time to do that work for someone else that gives them an extension kind of into their own research. Like I was really happy to enable this guy to work on his PhD project and also that he was kind of do that possibly.

[Too muffled to get context]

Scott: Hey Mark. So remind me when Against Competition was written again.

Mark: In 2006. It was written for this little journal that only did about five or six weeks of BHE and it definitely had a much larger lifeline than.

Male: Have we gone silent?

Mark: Yeah it's a nice comment. It's a nice situation question. I mean there are [too muffled].

Scott: So Mark maybe it would be good to give a brief overview of Against Competition as a – I wouldn’t necessarily say a theoretical stance even though it probably could be described that way, but I have a feeling you probably not want to say it that way, but not necessarily as a positional argument but as a recommendation for artists to consider their position in relation to other artists differently. Would you want to describe that a little bit or do you want me to describe that or are you feeling kind of..?

Mark: Yeah I can say a bit about it I think if people had a chance to read it a little bit I think it's a pretty straightforward, in fact, the examples are pretty clear and diverse. I feel at this point its only administrative work it's really not that much that I want to do entirely by myself. IT's not for me to have companies like yours when someone contacts me and asks me to host something or they have some structure they're trying to figure out a way share. Again like that one-one-one kind of smaller collaboration than a group situation of trying to just sort of endorse what individuals. But I think like the I'm kind of continually impressed by how much people are able to accomplish when they open themselves to making some part of their creative work allowing to get involved, organizing things that include other people, not always selfish like a solo show or a solo participation in a group show.

But really it's basically to make space for other people to realize that there's other people who have formal ideas and it's stupid not to learn from them and compare notes and benefit from most of the people putting their heads together.

[Too muffled for context]

Male: I have a question about it. It's a really broad question but maybe it's something you can respond to. In teaching it for I think a year and a half now like in several classes it's surprising to me how hard it is for, especially like the younger college students, to even grasp what the argument is that they really cannot even imagine the idea of it being the competition and that they be able to work together. And I'm curious whether you in the classroom or working with young people working with artists that talk about these ideas or what your experience has been in that and whether you're surprised that it's so alien still. I mean to me it just seems like a given at the brink really I find that it's engrained in our society in competition and you're essay just scratches the surface of what we really need to delve into to change the outlook.

Mark: Well I guess when I'm teaching I do ask students do you have assignments where you collaborate with other people are you allowed to do that, are you encouraged to do that? And some of them say yes some say no. Some of them have already been given the space to do that in their other courses. So if I'm the only other person teaching the course let them do that there're not that very many people in getting to them collaboratively.

I mean the other thing I always tell now to students is that I mean you're working with other people constantly. Like we came back from Thanksgiving break which was right before around the time they were doing their final project and when you share Thanksgiving with your family you need everyone to work together on this you know. Like someone brought the potato, someone goes out to eat. I mean it's just [inaudible 1:24:04] in every aspect of our lives not only in the art with regard to like a whole other by themselves and to their studies. A lot of the studies are setup so [inaudible 1:24:18] space and it's like usually as private as they can possibly make it. And that kind of separation is really encouraged.

And I remind the students that they're going to get out of art school and like you really need some kind of unity. I mean like you're going to be really soft if you have the greatest ideas and no one to talk to about them, no one to give feedback and let them know that the [inaudible 1:24:54] are maintained something until the school because you have the job market is horrible. And you have to tell them okay one of you will probably get a teaching job before the other does or get a teaching job if that's what you're trying to do. And you'll probably get this shitty budget of like $100 or $200 dollars to bring in a guest speaker. And after you hit up like your friend you went to school with because it enforces them to figure out and talk about what they do in front of a smaller audience or it gives you a break from having to talk it out to the class or they really. And you can take an opportunity to go through for your friends or you organize an exhibit together.

I don't know I think I've never have done that presentation so ideally that somebody else would do everything for you or it's really foreign to me. Like if you're interested in the community you're actually adding to publishing promotion, whatever you consider to bring to this. And you know I think like I mean young people are obviously going to run through [inaudible 1:26:30] themselves and [inaudible 1:26:33]. Again I don't know my industry is like with I think to get things done. Like going to gallery up in smoothing people tend to get opportunity.

[Audio muffled]

Renee: Can I respond to this as well.

Mark: Yeah.