Week 15: Loveland

Hi Everyone,

This Tuesday is another event in a year-long series of weekly conversations and exhibits in 2010 shedding light on examples of Plausible Artworlds.

Our discussions over the past weeks have foregrounded an understanding of plausible worlds as largely immaterial nodes of shared desire and exchange — as collective constructs in time, which exist as long as the collective will to pursue them is sustained. This conceptual mapping has gently helped avoid any excessively down-to-earth take on the notion of a “world”. But even worlds online and in time must contend with the question as to the relationship between “world” and “land”. So this week we’ll be talking with the Detroit-based instigators of LOVELAND, a micro real-estate project premised on using social microfunding and online tools to get people experimenting with and rethinking collective land use and ownership.

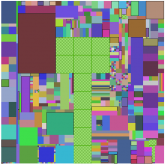

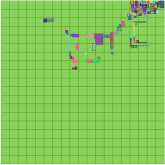

LOVELAND sells square inches of land in Detroit for $1 an inch. The project then uses these virtual, tiny-scale investments to fund real-world projects throughout the city. Inchvestors — that is, the people bankrolling the initiative one buck at a time — are able to access their land both on and offline, transforming the land in a mutually agreed-upon manner, with a goal of purchasing numerous pieces of real estate throughout the city and developing them around certain themes. Anyone involved can also transfer or sell inches to others.

Practically speaking, LOVELAND owns the property and merely extends social ownership to its inchvestors, making them less titleholders than stakeholders. The purchased inches are not legally binding and are not registered with the City of Detroit, keeping taxes and other unpleasantries of officialdom out of the picture. But it also puts the onus on the stakeholders to contend with existent legal instruments to ensure their interests are acknowledged. Art-historically, LOVELAND harks back to projects such as Gordon Matta Clark’s never fully realized “Fake Estates” — the interstitial gutterspaces he purchased from the City of New York in the 1970s — but significantly throws into the mix the unresolved issues of collective agency, common investment, and social use value.